| 1453 | The Ottoman Empire (established in 1301) advanced rapidly until it spread all the way from the Euphrates to the Danube. The Byzantine Empire was steadily reduced to a few territories and a small enclave around Constantinople. Unlike the Arabs, who thought the use of firearms dishonorable, the Ottomans became masters of artillery. In 1453 they brought their cannons to the gate of Constantinople and stormed the Christian capital after a siege. The Greek Emperor was killed; the great church of St. Sophia was plundered of its treasure and turned into a mosque. The Fall of Constantinople marks the end of the Middle Ages

|

| The Ottomans |

| 1455 | The earliest Germanic version of the Bible was the Gothic translation from Latin and Greek undertaken by Ulfilas (ca. 381). From Ulfilas came much of the Germanic Christian vocabulary that is still in use today. Later Charlemagne would foster Frankish (Germanic) biblical translations in the ninth century. Over the years, prior to the appearance of the first printed German Bible in 1466, various German and German dialect translations of the Scriptures were published. The Augsburger Bibel of 1350 was a complete New Testament, while the Wenzel Bible (1389) contained the Old Testament in German. Johannes Gutenberg's so-called 42-line Bible, printed in Mainz in 1455, was in Latin. About 40 copies exist today in various states of completeness. It was Gutenberg's invention of printing with movable type that made the Bible, in any language, vastly more influential and important. It was now possible to produce Bibles (and other books) in greater quantities at a lower cost |

| 1466 | Before Martin Luther was even born, a German-language Bible was published in 1466, using Gutenberg's invention. Known as the Mentel Bibel, this Bible was a literal translation of the Latin Vulgate. Printed in Strassburg, the Mentel Bibel appeared in some 18 editions until it was replaced by Luther's new translation in 1522 |

| 1492 | Columbus sailed from Palos de la Frontera on 3 August, 1492. His flagship, the Santa Maria had 52 men aboard while his other two ships, the Nina and Pinta each held 18 men. The expedition made a stop at the Canary Islands and on 6 September 1492 sailed westward. The weather during the journey was pleasant but by 10 October, after 34 days at sea and convinced that at any moment they would reach and fall off the edge of a world they believed was flat, the sailors were ready to mutiny. Columbus was able to convince the mutineers to wait 3 more days and the very next day they saw tree branches floating in the water, a sign that land was close. After making landfall in the Bahamas at dawn on 12 October 1492, Columbus explored the coasts and named a large number of islands, including Cuba and La Espanola. When he went ashore he was puzzled because the 'easterners' were not what Marco Polo described them to be on his return to Europe in 1295 after spending 20 years in the Orient, nor did Columbus see any 'pagodas' with golden roofs |

| The Columbus Navigation Homepage

What are some Christopher Columbus Facts? - suggested by Caitlin Walters

|

| In the spring of 1492, shortly after the Moors were driven out of Granada, Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain expelled all the Jews from their lands and thus, by a stroke of the pen, put an end to the largest and most distinguished Jewish settlement in Europe. The expulsion of this intelligent, cultured, and industrious class was prompted only in part by the greed of the king and the intensified nationalism of the people who had just brought the crusade against the Muslim Moors to a glorious close. The real motive was the religious zeal of the Church, the Queen, and the masses. The official reason given for driving out the Jews was that they encouraged the Marranos to persist in their Jewishness and thus would not allow them to become good Christians

|

|

Jewish History Sourcebook from which this extract has been taken |

| Vasco da Gama was born in Sines, Portugal in 1469. Being the son of the towns governor, he was educated as a nobleman and served in the court of King Joao II. Da Gama also served as a navel officer, and in 1492 he commanded a defense of Portuguese colonies from the French on the coast of Guinea. Da Gama was then given the mission to the take command of the first Portuguese expedition around Africa to India. When Vasco da Gama set out on July 8, 1497 he and his crew planned and equipped four ships. Goncalo Alvares commanded the flagship Sao (Saint) Gabriel. Paulo, da Gama's brother, commanded the Sao Rafael. The other two ships were the Berrio and the Starship. Most of the men working on the ship were convicts and were treated as expendable. On the voyage, da Gama set out from Lisbon, Portugal, rounded the Cape of Good Hope on November 22, and sailed north. Da Gama made various stops along the coast of Africa in trading centers such as Mombasa, Mozambique, Malindi, Kenya, and Quilmana. As the ships sailed along the east coast of Africa, many conflicts arose between the Portuguese and the Muslims who had already established trading centers along the coast. The Muslim traders in Mozambique and Mombasa did not want interference in their trade centers. Therefore, they perceived the Portuguese as a threat and tried to seize the ships. In Malindi, on the other hand, the Portuguese were well received, because the ruler was hoping to gain an ally against Mombasa, the neighboring port. From Malindi, da Gama was accompanied the rest of the way to India by Ahmad Ibn Majid, a famous Arab pilot. Vasco da Gama finally arrived in Calicut, India on May 20, 1498 |

| Hapsburg from which this extract has been taken |

| 1493 | Djuradj Crnojevic (1490-96), Ivan Crnojevic's elder son, was an educated ruler. He is most famous for a single historical act: he used the printing press brought to Cetinje by his father to print the first books in southeastern Europe, in 1493. The Crnojevic printing press marked the beginning of the printed word among the southern Slavs. The press operated from 1493 through 1496, turning out religious books of which five have been preserved: Oktoih prvoglasnik, Oktoih petoglasnik, Psaltir, Molitvenik and Cetvorojevandjelje. Djuradj managed the printing of the books, wrote prefaces and afterwords, and developed sophisticated tables of Psalms with the lunar calendar. The books from the Crnojevic press were printed in two colors, red and black, and were richly ornamented. They served as models for many of the subsequent books printed in cyrillic. The end of the fifteenth century and of Djuradj's rule mark the end of the Crnojevic dynasty |

| Zeta (Montenegro) under the third Montenegrin dynasty, the Crnojevic (1427-1516) |

| 1500 | Birth of Charles V of Hapsburg, who became Lord of the Netherlands in 1515, King of Spain in 1516, and was elected Holy Roman Emperor (German-speaking region) in 1519. He ruled most of Europe until his abdication in 1556. Most of the Low Countries had been acquired by the marriage of the Hapsburg Maximilian to Mary of Burgundy. The marriage of their son, Philip I, to Joanna of Castile, brought Philips elder son, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, to the throne of Spain. The marriage of Charless younger brother, Ferdinand, to Anna, daughter of Louis II of Bohemia and Hungary, strengthened the Hapsburg claim to these possessions after the death (1526) of Louis at Mohács. Hapsburg power reached its zenith under Charles V. The reigns of Maximilian I and Charles V, while encompassing the height of Hapsburg power, also witnessed the emergence of the enduring struggles that eventually sapped Hapsburg strength. These included the defense of Central Europe against the Turks; the support of the Catholic Church against the Protestant Reformation; and the defense of the dynastic position against the rise of France |

|

Vasco da Gama Arrives in India - 1498 from which this extract has been taken |

| 1509 | Henry VIII (1491-1547) ascends the throne of England. He was the second son and third child of his father, Henry VII. His elder brother Arthur died in April, 1502, and consequently Henry became heir to the throne when he was not yet quite eleven years old. It has been asserted that Henry's interest in theological questions was due to the bias of his early education, since he had at first been destined by his father for the Church. But a child of eleven can hardly have formed lifelong intellectual tastes, and it is certain that secular titles, such as those of Earl Marshal and Viceroy of Ireland, were heaped upon him when he was five. On the other hand there can be no question as to the boy's great precocity and as to the liberal scope of the studies which he was made to pursue from his earliest years.

|

| Henry VIII from which this extract has been taken |

| 1517 | Martin Luther (1483-1546) dealt the symbolic blow that began the Reformation when he nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of the Wittenberg Church. That document contained an attack on papal abuses and the sale of indulgences by church officials. But Luther himself saw the Reformation as something far more important than a revolt against ecclesiastical abuses. He believed it was a fight for the gospel. Luther even stated that he would have happily yielded every point of dispute to the Pope, if only the Pope had affirmed the gospel. And at the heart of the gospel, in Luther's estimation, was the doctrine of justification by faith - the teaching that Christ's own righteousness is imputed to those who believe, and on that ground alone, they are accepted by God |

|

Martin Luther [link suggested by Brooke Folliot]

|

| 1520 | An expedition sent by Spain to the Caribbean in 1518 but under the leadership of Grijalva touched the coast of Mexico, and brought home metallic objects and evidences of superior culture. Velazquez determined to send a more numerous squadron to the Mexican coast. Hernando Cortés (c.1485-1547), then one of Velazquez's favourites, was named as the commander, a choice which created no little envy. Cortés entered into the enterprise with zeal and energy, sacrificing with a great deal of ostentation a considerable part of his fortune to equip the expedition. Eleven vessels were brought together, manned with well-armed men, and horses and artillery were embarked. At the last moment Velazquez, whose suspicions were aroused by the action of Cortés, instigated by his surroundings, attempted to prevent the departure. It was too late; Cortés, after the example set by Quintero, slipped away from the Cuban coast and thus began the conquest of Mexico which he achieved by 1520 |

| Hernando Cortés from which this extract has been taken |

| 1520-22 | It was the Portuguese who first sailed round Africa and realised Columbus' dream of reaching the Far East by sea. But this route was one which could not be used by the Spanish because in the famous Treaty of Tordesillas, it had been stipulated that the southernmost limit for navigation by Castilian vessels off the Atlantic Coast of Africa was Cape Bojador. Starting at the beginning of the sixteenth century, the Spanish monarchy intensified efforts to find a strait dividing the continent of America which would allow passage to what would be called the Pacific and further east, the Moluccas, or Spice Islands. The Crown assembled a flotilla of five vessels to pursue this goal and command fell to a Portuguese, Ferdinand Magellan; it was he who went on to persuade Spain that the project was feasible, discover at the southern tip of America the strait which would subsequently bear his name and carry on to the Moluccas, where he in fact died. It was Juan Sebastian Elcano who with just one ship, went on round the world for the first time, returning to Spain along the Portuguese route. It is proof enough of the exceptional difficulty of this crossing that only 18 men out of the 285 who had set out came back in the Victoria |

| 1523 | translation of the New Testament into French by Jacques Lefèvre d'Etaples (Stapulensis) (c.1455-1536) is published in Paris, 1523 |

| Jacques Lefèvre d'Etaples |

| 1529 | The successful repulsion of the Turkish besiegers in 1529 had earned the city of Vienna great international prestige. Although Vienna was not conquered, the siege was to have a dramatic impact on its physical structure. As early as 1530 work was undertaken to replace the now inefficient medieval city walls by modern fortifications and bastions, built on the Italian model. Travelogues and descriptions from the sixteenth century already testify to the city's metropolitan character with strikingly tall buildings, but also narrow lanes, and altogether vibrant urban life. However, this also marked the beginning of the end of late medieval burgher autonomy. The renewed rise to glory of the Habsburgs, who returned to being Holy Roman Emperors in 1438, left little space for that. Even the beginnings of Vienna, under the Babenbergs, had been marked by the city's role as a residence, and this tendency became more strongly apparent still with the dawn of the early modern age. At the time, Vienna became the capital of the Holy Roman Empire and the residence of the Emperor, and this is reflected not least in the fact that all building activity was dominated by the court, the aristocracy and the church |

| The period of the Turkish sieges (1529-1683) from which this extract has been taken |

| 1534 | Die Luther Bibel (Neues Testament appeared earlier in 1522). The most influential German Bible, and the one that continues to be most widely used in the Germanic world today (last official revised edition in 1984), was translated from the original Hebrew and Greek by Martin Luther (1483-1546) in the record time of just ten weeks (New Testament) during his involuntary stay in the Wartburg Castle near Eisenach, Germany. Luther's first complete Bible in German appeared in 1534. He continued to revise his translations up until his death. In response to Luther's Protestant Bible, the German Catholic Church published its own versions, most notably the Emser Bibel, which became the standard German Catholic Bible. Luther's German Bible also became the primary source for other northern European versions in Danish, Dutch, and Swedish |

| 1536 | John Calvin (1509-1564) publishes his Institutes of Christian Religion |

| Calvinism |

| 1540 | Pope Paul III authorizes the Society of Jesus, founded by Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556). The Society was not founded with the avowed intention of opposing Protestantism. Neither the papal letters of approbation nor the Constitutions of the order mention this as the object of the new foundation. When Ignatius began to devote himself to the service of the Church, he had probably not even heard of the names of the Protestant Reformers. His early plan was rather the conversion of Mohammedans, an idea which, a few decades after the final triumph of the Christians over the Moors in Spain, must have strongly appealed to the chivalrous Spaniard. The name "Societas Jesu" had been born by a military order approved and recommended by Pius II in 1450, the purpose of which was to fight against the Turks and aid in spreading the Christian faith. The early Jesuits were sent by Ignatius first to pagan lands or to Catholic countries; to Protestant countries only at the special request of the pope and to Germany, the cradle-land of the Reformation, at the urgent solicitation of the imperial ambassador. From the very beginning the missionary labours of the Jesuits among the pagans of India, Japan, China, Canada, Central and South America were as important as their activity in Christian countries. As the object of the society was the propagation and strengthening of the Catholic faith everywhere, the Jesuits naturally endeavored to counteract the spread of Protestantism. They became the main instruments of the Counter-Reformation; the re-conquest of southern and western Germany and Austria for the Church, and the preservation of the Catholic faith in France and other countries were due chiefly to their exertions. |

| The Jesuits from which the above extract has been taken |

| 1541 | Calvin becomes the reformer and de facto ruler of Geneva until his death |

| John Calvin |

| 1543 | Nicholas Copernicus (1473-1543) publishes De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium |

| Nicholas Copernicus |

| Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) publishes De Humani Corporis Fabrica |

| Andreas Vesalius |

| 1545 | Beginning of the Council of Trent, which met 1545-1547, 1551-1552, 1562-1563. The nineteenth ecumenical council opened at Trent on 13 December, 1545, and closed there on 4 December, 1563. Its main object was the definitive determination of the doctrines of the Church in answer to the heresies of the Protestants; a further object was the execution of a thorough reform of the inner life of the Church by removing the numerous abuses that had developed in it |

| Council of Trent |

| 1547 | Edward VI (153753) becomes king of England. Edward succeeded his father to the throne at the age of nine. Henry had made arrangements for a council of regents, but the council immediately appointed Edwards uncle, Edward Seymour, earl of Hertford (later duke of Somerset), as lord protector. Henrys absolutism was relaxed by a liberalization of the treason and heresy laws. Tempering the reforming zeal of Thomas Cranmer, archbishop of Canterbury, the government moved slowly toward Protestantism. The Act of Uniformity (1549), which required use of the first Book of Common Prayer, increased contention between Roman Catholics and reformers, and an unsuccessful rebellion occurred in the west. The dissolution of chantries and the destruction of relics, both begun under Henry, proceeded apace. Somerset won a victory over the Scots at Pinkie (1547) but failed to persuade them to agree to a marriage between Edward and Mary Queen of Scots. The Scots instead strengthened their alliance with France, the power that increasingly threatened Englands safety. War between France and England broke out in 1549 over the possession of Boulogne. |

| Edward VI from which this extract has been taken |

| 1551 | Foundation of the University of Lima, Peru. Lima was founded on its present site in 1535 by the Spanish soldier Francisco Pizarro, and the fountain in the central square dates from 1651. An earthquake in 1746 destroyed all of the colonial structures on the plaza, which were rebuilt in subsequent decades. Limas cathedral (begun in 1746) faces the plaza and contains a glass coffin said to hold Pizarros remains |

| The University of Mexico at Mexico City, founded in 1551 by the Spanish king Charles I (Holy Roman Emperor Charles V) |

| 1553 | Michael Servetus (1511-1553), a Spaniard martyred in the Reformation for his criticism of the doctrine of the trinity and his opposition to infant baptism, has often been considered an early unitarian. Sharply critical though he was of the orthodox formulation of the trinity, Servetus is better described as a highly unorthodox trinitarian. Still, aspects of his theology for example, his rejection of the doctrine of original sin did influence those who later founded unitarian churches in Poland and Transylvania. Public criticism of those responsible for his execution, the Reform Protestants in Geneva and their pastor, John Calvin, moreover, inspired unitarians and other groups on the radical left-wing of the Reformation to develop and institutionalize their own heretical views. Widespread aversion to Servetus' death has been taken as signaling the birth in Europe of religious tolerance, a principle now more important to modern Unitarian Universalists than antitrinitarianism. Servetus is also celebrated as a pioneering physician. He was the first to publish a description of the blood's circulation through the lungs |

| Michael Servetus from which this extract has been taken |

| 1555 | The Peace of Augsburg (1555) represented a victory for the German princes, granted recognition to both Lutheranism and Roman Catholicism in Germany, and gave each ruler the right to decide the religion to be practiced within his state. Subjects not of this faith could move to another state with their property, and disputes between the religions were to be settled in court. The Protestant Reformation strengthened the long-standing trend toward particularism in Germany. German leaders, whether Protestant or Catholic, became yet more powerful at the expense of the central governing institution, the empire. Protestant leaders gained by receiving lands that formerly belonged to the Roman Catholic Church, although not to as great an extent as, for example, would occur in England. Each prince also became the head of the established church within his territory. Catholic leaders benefited because the Roman Catholic Church, in order to help them withstand Protestantism, gave them greater access to church resources within their territories. Germany was also less united than before because Germans were no longer of one faith, a situation officially recognized by the Peace of Augsburg. The agreement did not bring sectarian peace, however, because the religious question in Germany had not yet been settled fully |

| 1558 | Elizabeth I becomes Queen of England until her death in 1603. When Elizabeth became Queen, it was widely believed that she would restore the Protestant faith in England. Her sister Mary's persecution of Protestants had done much damage to the standing of Catholicism in England, and the number of Protestants in the country was steadily increasing. Although Elizabeth had adhered to the Catholic faith during her sister's reign, she had been raised a Protestant, and was committed to that faith. Elizabeth's religious views were remarkably tolerant for the age in which she lived. She believed sincerely in her own faith, but she also believed in religious toleration, and that Catholics and Protestants were both part of the same faith. "There is only one Christ, Jesus, one faith" she exclaimed later in her reign, "all else is a dispute over trifles." She also declared that she had "no desire to make windows into men's souls".

Throughout her reign, Elizabeth's main concern was the peace and stability of the realm, and religious persecution was only adopted when certain religious groups threatened this peace. It was unfortunate for Elizabeth that so many of her contemporaries did not share her views on toleration, and she was forced by circumstance to adopt a harsher line towards Catholics than she intended or wanted. Elizabeth's toleration of Catholics, and her refusal to make changes to the Church she established in 1559, has led some historians to doubt her commitment to her faith - even to assert that she was an atheist, but such statements are misleading. Elizabeth wanted a Church that would appeal to both Catholics and Protestants, and did not want to move the Church in a more Protestant direction, thus making it more difficult for Catholics to accept the Church than it was already. The form of worship also suited the Queen's conservative religion. She had little sympathy with Protestant extremists who wanted to strip the Church of it's finery, ban choral music, vestments and bell-ringing, and liked her Church just the way it was

|

| Elizabeth I from which this extract has been taken |

| 1562 | Beginning of wars of religion in France that last until 1589 when Henry IV of Navarre ascends the throne. The religious wars began with overt hostilities in 1562 and lasted until the Edict of Nantes in 1598. It was warfare that devastated a generation, although conducted in rather desultory, inconclusive way. Although religion was certainly the basis for the conflict, it was much more than a confessional dispute. Une foi, un loi, un roi, (one faith, one law, one king). This traditional saying gives some indication of how the state, society, and religion were all bound up together in people's minds and experience. There was not the distinction that we have now between public and private, between civic and personal. Religion had formed the basis of the social consensus of Europe for a millenium. Since Clovis, the French monarchy in particular had closely tied itself to the church - the church sanctified its right to rule in exchange for military and civil protection. France was "the first daughter of the church" and its king "The Most Christian King" ,le roy tres chretien, and no one could imagine life any other way. "One faith" was viewed as essential to civil order - how else would society hold together? And without the right faith, pleasing to God who upholds the natural order, there was sure to be disaster. Heresy was treason, and vice versa. Innovation caused trouble. The way things were is how they ought to be, and new ideas would lead to anarchy and destruction. No one wanted to admit to being an "innovator". The Renaissance thought of itself as rediscovering a purer, earlier time and the Reformation needed to feel that it was not new, but just a "return" to the simple, true religion of the beginnings of Christianity |

| Wars of Religion from which this extract has been taken |

| 1564 | Throughout Calvin's rule, Geneva was protected by Bern, which had acquired the territory immediately surrounding the city in 1535; however in 1564, the year of Calvin's death, Bern was forced to cede this territory back to Savoy under the Treaty Of Lausanne. Geneva was an associated territory, not a full member of the Swiss Federation. The Canton of Geneva consisted of several patches of territory surrounded by Savoyard territory, separated from the Swiss Confederation by a couple of kilometers. In 1602 the Savoyards tried to scale the city walls under cover of darkness and take the city by surprise (the Duke of Savoy was a Catholic). The town, alterted in time, overwhelmed the intruders. Geneva continued to attract (Calvinist) religious refugees and it was here that English Puritan exiles translated what is called the Geneva Bible in 1599 |

| Death of Michelangelo (b. 1475) |

| Michelangelo Buonarroti

Michelangelo Buonarroti |

| Birth of Galileo (d. 1642) |

| Galileo Galilei |

| Birth of Shakespeare (d. 1616) |

| William Shakespeare |

| 1568 | Beginning of the revolt of the northern Low Countries against Philip II, King of Spain. Philip had committed the government to his aunt, Margaret of Parma, the nobles, chafed because of their want of influence, plotted and trumped up grievances. They protested against the presence in the country of several thousands of Spanish soldiers, against Cardinal de Granvelle's influence with the regent, and against the severity of Charles V's decrees against heresy. Philip recalled the Spanish soldiers and the Cardinal de Greavelle, but he refused to mitigate the decrees and declared that he did not wish to reign over a nation of heretics. The difficulties with the Iconoclasts having broken out he swore to punish them and sent thither the Duke of Alva with an army, whereupon Margaret of Parma resigned. Alva behaved as though in a conquered country, caused the arrest and execution of Count Egmont and de Hornes, who were accused of complicity with the rebels, created the Council of Troubles, which was popularly styled the "Council of Blood", defeated the Prince of Orange and his brother who had invaded the country with German mercenaries, but could not prevent the "Sea-beggars" from capturing Brille. He followed up his military successes but was recalled in 1573. His successor Requesens could not recover Leyden. Influenced by the Prince of Orange the provinces concluded the "Pacification of Ghent" which regulated the religious situation in the Low Countries without royal intervention. The new governor, Don Juan, upset the calculations of Orange by accepting the "Pacification ", and finally the Prince of Orange decided to proclaim Philip's deposition by the revolted provinces. The king replied by placing the prince under the ban; shortly afterwards he was slain by an assassin (1584). Nevertheless, the united provinces did not submit and were lost to Spain. Those of the South, however, were recovered one after another by the new governor, Alexander Farnese, Prince of Parma. But he having died in 1592 and the war becoming more difficult against the rebels, led by the great general Maurice of Nassau, son of William of Orange, Philip II realized that he must change his policy and ceded the Low Countries to his daughter Isabella, whom he espoused to the Archduke Albert of Austria, with the provision that the provinces would be returned to Spain in case there were no children by this union (1598). The object of Philip's reign was only partly realized. He had safeguarded the religious unity of Spain and had exterminated heresy in the southern Low Countries, but the northern Low Countries were lost to him forever |

| Philip II from which this extract has been taken |

| 1571 | Birth of Johannes Kepler (d. 1630) |

| Johannes Kepler |

| In the 1560s, the Ottoman Empire pursued a policy of expansion, based on her military power. While the Great Siege of Malta (1565) entered the history book as an Ottoman defeat, it had tested to the limit the will of the Christian nations to resist. In the following year, the Aegean Islands fell to an Ottoman fleet without resistance; even Venice and Genoa, who owned these islands, failed to respond. In 1566, Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent died; his successor, Selim II, continued his predecessor's expansionist policy. Philip II of Spain aware that further conflict was inevitable, and unable to count on the loyalty of his Morisco minority, only nominally Christian and living in the territory which had formed the Kingdom of Granada, who might revolt once a Spanish-Ottoman war broke out, provoked the Morisco Revolt (1568-1571) which was put down by an army led by Don Juan d'Austria, illegitimate son of the Holy Roman emperor Charles V and half brother of Philip II. A naval alliance between Spain, the Papal State and Venice, together with Genoa and Savoy-Piemont led to a combined fleet, under the command of Don Juan d'Austria, crushing the Ottoman fleet off Lepanto on the coast of Greece in 1571. Despite the victory, the alliance failed to act upon it, and an Ottoman force invaded and conquered the hitherto Venetian island of Cyprus (1571), which Venice ceded in a 1573 treaty. Don Juan d'Austria retook Tunis for Spain, but he was recalled and in 1574 the Spanish permitted the city to fall to the Ottoman forces without resistance. Again, as in the case of the Great Siege of Malta, the will of the Christian states to hold on to their possessions in the eastern and southern shores of the Mediterranean was lacking. The reluctance of the Alliance to follow up on its victory was due in no small part on the enormous costs involved. In 1574, Philip II informed the newly elected Pope, Gregory XIII, that the defence of Malta and the maintenance of the fleet would cost him two million ducats annually |

| 1572 | New star (nova stella, or nova) in Cassiopeia, fully described by Tycho Brahe |

| Tycho Brahe |

| St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, in which thousands of French Protestants (Huguenots) were killed |

| The Massacre of St. Bartholomew's Day |

| 1575 | Leiden University was founded in 1575, as an unexpected gift to the city. In 1574, Prince William of Orange took the first steps towards establishing the university, when he wrote a letter to the States of Holland. In this letter he proposed that as a reward for the towns brave resistance against the Spanish invaders a university be founded which would serve as a staunch support and maintenance of the freedom and good lawful government of the country. On February 8, 1575, the university was founded, and was later granted the motto Praesidium Libertatis, or Bastion of Liberty |

| Leiden University from which this extract has been taken |

| 1577 | Comet of 1577, fully described by Tycho Brahe |

| 1582 | Pope Gregory XIII (Ugo Buoncompagni (1502-1585) institutes the Gregorian Calendar. The Gregorian Calendar is a revision of the Julian Calendar necessary to correct for a drift in the dates of important religious fesitvals (primarily Easter) and to prevent any further drift in the dates. The important effects of the change were:

- drop 10 days from October 1582, to realign the Vernal Equinox with 21 March

- change leap year selection so that not all years ending in "00" are leap years

- change the beginning of the year to 1 January from 25 March

The change in the number frequency of leap years (by dropping 3 every 400 years) slightly changes the average year length to something closer to reality. The new calendar was adopted essentially immediately within Catholic countries. In Protestant countries, where papal authority was neither recognized not appreciated, adoption came more slowly. England finally adopted the new calendar in 1752, with eleven days removed from September. An additional day arose from the fact that the old and new calendars disagreed on whether 1700 was a leap year. The Gregorian year length gives an error of one day in approximately 3,225 years |

| Pope Gregory XIII |

| 1588 | Spanish Armada defeated by the weather and the English fleet |

| The Spanish Armada |

| 1589 | Henry of Navarre (1553-1610) becomes the first Bourbon king, Henry IV, of France. Henry IV was a popular king who ruled France during the religious strife of the Reformation. Although a notorious philanderer, he was renowned for his common sense and political acumen, and for his valiant military leadership. Born a Catholic, Henry converted to Protestantism and led the Huguenots (Protestants) in religious wars against the Catholics. In 1572, to calm religious unrest, he married the Catholic king's sister, Margaret of Valois, and later became heir to the throne.

But after the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre of Protestants, Henry continued to lead the Huguenots, causing the Catholics to protest his succession to the throne in 1589. He enforced his claim with arms, and then reconverted to Catholicism to unify the country. Henry restored peace and prosperity to France after decades of civil and foreign wars. He fostered religious tolerance and proclaimed the Edict of Nantes, giving political equality and religious freedom to the Huguenots. He increased agricultural production, industry, and foreign trade, but was assassinated by a Catholic extremist in 1610 |

| Henry IV, King of France |

| 1597 | Johannes Kepler publishes Cosmographic Mystery |

| 1598 | Edict of Nantes, under which Protestants in France are allowed to practice their religion in peace |

| Edict of Nantes |

| 1600 | Giordano Bruno burned at the stake in Rome |

| Giordano Bruno: The Forgotten Philosopher |

| William Gilbert (1540-1603) publishes On the Magnet |

| William Gilbert |

| 1603 | Elizabeth I, Queen of England, dies, and with her the Tudor line. Her successor is James I of the House of Stuart, who rules until 1625 |

Humanism ::

- Although the term 'humanism' was coined in 1808 by F.J. Niethammer, to describe a program of study distinct from science and engineering, umanista, or 'humanist', as employed in the fifteenth century, described a professional group of teachers whose subject matter consisted of those areas that were called litterae humanitatis or studia humanitatis. The studia humanitatis originated in the middle ages and comprised the trivium and the quadrivium, educational disciplines that lay outside theology and natural science. Humanism was opposed to a particular brand of logic known as Scholasticism (where language was used to produce certainty, focussing on syllogism, which is the construction of a truthful conclusion from truthful premises); rather, it developed a science of logic based on discovering arguments that would persuade people of the truth of what they were saying rather than convincing them of the certainty of that truth. While the 'humanist' scholars of the Renaissance made great strides and discoveries in this field, humanistic studies were really a product of the middle ages, of what others have called the Italian proto-Renaissance, of those who looked to Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch) (1304-1374) as their inspiration.

The movement spread throughout Europe. Steven Kreis writes:

"Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536), one of the greatest humanists, occupied a position midway between extreme piety and frank secularism. Petrarch represented conservative Italian humanism. Robust secularism and intellectual independence reached its height in Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527) and Francesco Guicciardini (1483-1540). Rudolphus Agricola (1443-1485) may be regarded as the German Petrarch. In England, John Colet (c.1467-1519) and Sir Thomas More (1478-1535) were early or conservative humanists, Francis Bacon (1561-1626) represented later or agnostic and skeptical humanism. In France, pious classicists like Lefèvre d'Étaples (1453-1536) were succeeded by frank, urbane, and devout skeptics like Michel Montaigne (1533-1592) and bold anti-clerical satirists like François Rabelais (c.1495-1533)."

We paraphrase below part of Ilona Berkovits' Illuminated Manuscripts from the library of Matthias Corvinus (1964): Extract. pp. 9-53:

"Like the Italian Renaissance princes, [Matthias Corvinus (1458-1490)] recognized that by surrounding himself with scholars and artists his reign acquired a superb brilliance. However, the roots of Hungarian humanist learning can be traced to the era of Matthias's father, Governor Johannes Hunyadi, the valiant general who defeated the Turks, and to the period of the Hungarian King Sigismund of the House of Luxembourg (1387-1437). Hungarian humanism served the interests of royal power and the policy of centralization; its zealous advocates were for the most part foreigners and members of the ecclesiastic intelligentsia who usually rose to occupy high offices. The foundation of Matthias's famous library at Buda was chiefly due to the influence which Johannes Vitéz exerted over the King. Vitéz was the founder, organizer and guide of Hungarian humanism. During Sigismund's reign Italian humanists had already presented themselves at court: Ambrogio Traversari, Antonio Loschi and Francesco Filelfo had all dedicated works to him. The arrival of the eminent Italian humanist, Pier Paolo Vergerio, marked the (real) beginning of Hungarian humanism, for he was the first Italian humanist to stay for several decades in Hungary, where he became very friendly with Vitéz."

Francis I (14941547) called the Father and Restorer of Letters (le Père et Restaurateur des Lettres), crowned King of France in 1515 in the cathedral at Reims is considered to be France's first Renaissance monarch. A number of his tutors, such as Desmoulins, his Latin instructor, and Christophe de Longeuil were schooled in the new ways of thinking and they attempted to imbue Francis with it. Francis' mother also had a great interest in Renaissance art, which she passed down to her son. One certainly cannot say that Francis received a humanist education; most of his teachers had not yet been affected by the Renaissance. One can, however, state that he clearly received an education more oriented towards humanism than any previous French king. Francis became a major patron of the arts. He lent his support to many of the greatest artists of his time and encouraged them to come to France. Some did work for him, including such greats as Andrea del Sarto, and Leonardo da Vinci, who Francis convinced to leave Italy in the last and least productive part of his life. While Leonardo did little painting in his years in France, he brought with him many of his great works, such as the Mona Lisa, and these stayed in France upon his death. Francis was also renowned as a man of letters. When Francis comes up in a conversation among characters in Castiglione's Book of the Courtier, it is as the great hope to bring culture to the war-obsessed French nation. Not only did Francis support a number of major writers of the period, he was a poet himself, if not one of immense quality. Francis worked hard at improving the royal library. He appointed the great French humanist Guillaume Budé as chief librarian, and began to expand the collection. Francis employed agents in Italy looking for rare books and manuscripts, just as he had looking for art works.

In England, the neo-Platonist 'School of Night', led by Thomas Harriot (15601621), English mathematician and astronomer, and former tutor to Walter Raleigh, included John Florio (1553?-1625), the translator of Montaigne, and a friend of Giordano Bruno (1548-1600). Bruno's exceptional intellect and powers of memory brought him to the attention of Rome. He was called upon to demonstrate his abilities to the Pope. During this period he may also have come under the influence of Giovanni Battista Della Porta (1536-1615), a Neapolitan polymath who published an important work Magiae naturalist on popular science, cosmology, geology, optics, plant products, medicines, poisons, cooking, transmutation of the metals (not however confining transmutation to the alchemistical signification, but including chemical changes generally), distillation, artificial gems, the magnet and its properties, known remedies for a host of ailments, cosmetics used by women, fires, gunpowders, Greek fires (including preparations of Marcus Gracchus) and on invisible and clandestine writing. Much of this he derived from ancient texts from the time of Theophrastus and Aristotle. Bruno was attracted to new streams of thought, among which were the works of Plato and Hermes Trismegistus, both resurrected in Florence by Marsilio Ficino in the late fifteenth century. Hermes Trismegistus was thought to be a gentile prophet who was a contemporary of Moses. The works attributed to him in fact date from the turn of the Christian era. Because of his heterodox tendencies, Bruno came to the attention of the Inquisition in Naples and in 1576 he left the city to escape prosecution. When the same happened in Rome, he fled again, this time abandoning his Dominican habit. For the next seven years he lived in France, lecturing on various subjects and attracting the attention of powerful patrons. From 1583 to 1585 he lived at the house of his patron, Michel de Castelnau, seigneur de Mauvissiere, the longest-serving French ambassador to Elizabeth I. During this period Bruno published Cena de le Ceneri and De l'Infinito, Universo e Mondi (both in 1584). In Cena de le Ceneri, Bruno defended the heliocentric theory of Copernicus. It appears that he did not understand astronomy very well, for his theory is confused on several points. In De l'Infinito, Universo e Mondi he argued that the universe was infinite, that it contained an infinite number of worlds, and that these are all inhabited by intelligent beings.

Other members of the 'School of Night' included the explorer Richard Hakluyt (c.1552-1616) and Shakespeare's patron Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton (1573-1624). Bruno's presence may in fact have catalyzed the formation of the 'School of Night'. To those memorable dinners at the French embassy came Walter Raleigh (1552-1618), Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593), Philip Sidney (1554-1586), and Fulke Greville, Lord Brooke (1554-1628); Florio, Bruno and Mauvissiere played host. The conversation, according to Bruno's Cena de le ceneri, dwelt on the new Copernican system of astronomy, and its philosophical implications. Florio's Montaigne was on William Shakespeare's shelves, we know, for there is a copy with his hooked-S signature in it. Another member was Florio's publisher, Edward Blount (c.1565-1632?), one of the stationers in Paules churchyard implicated with Marlowe in Thomas Kyd's accusations of atheism. Together with Isaac and William Jaggard, Blount was the publisher of Shakespeare's First Folio (1623). Matthew Roydon (1580-1622) the poet and William Warner (1558?1609), a scientist who probably anticipated Harvey in his discovery of the circulation of the blood, were associates of Marlowe's and also of other members of the 'School of Night'. The 'wizard' John Dee (1527-1608/9), whose magical entertainment of the emperor Rudolf II at his court at Prague in the late eighties probably formed the basis of the corresponding scene in Doctor Faustus, was also closely connected with the group. Although Dee himself published little, the work of his disciple Robert Fludd gives us a good idea of the nature of his thought. Fludd developed a remarkable memory system called the Theatrum Mundi, the Theatre of the World. Frances Yates believes that the architecture of the Globe Theatre was partly inspired by this system. George Chapman, the translater of Homer, was another member of the 'School'. Some have speculated that Chapman was Shakespeare's 'rival poet', though others, notably A.L. Rowse, believe Marlowe himself better fits the part. In either case, the rivalry might explain the peculiar relationship of Shakespeare to the group, one of close interest, admiration, and intimate knowledge, but also a certain personal distance and even hostility. Chapman's close relationship with Marlowe is attested by his completing of Marlowe's Hero and Leander, which had been interrupted by Marlowe's death.

During the late fouteenth and early fifteenth century, humanism emerged in Florence. With the patronage of the powerful Medici family, Coluccio Salutati (1331-1406) and Leonardo Bruno (Aretino) (1369-1444) defined the studia humanitatis as an educational program based on the study of Greek and Roman authors. The goal of their civic humanism was to train aristocratic men for public affairs, philosophy, history, and poetry. Men and women alike could study these subjects, but only men could take up rhetoric, science, and mathematics. The humanists looked to the Greek and Latin classics for the lessons one needed to lead a moral and effective life and the best models for a powerful Latin style particularly Cicero. They developed a new, rigorous kind of classical scholarship, with which they corrected and tried to understand the works of the Greeks and Romans, which seemed so vital to them. Both the republican elites of Florence and Venice and the ruling families of Milan, Ferrara, Mantua and Urbino hired humanists to teach their children classical morality and to write elegant, classical letters, histories, and propaganda. Two foundational figures in this project, as it developed beyond Florence, were Guarino Veronese (1374-1406) in Ferrara and Vittorino da Feltre (1373-1446) at Mantua.

Although the recovery of Greek texts began at the start of the middle ages in Europe, Renaissance humanism is seen as the movement which introduced Europeans, in particular Italians, to a vast range of quantity of classical Greek texts particularly associated with the arrival of Byzantine scholars, initially to teach but, from 1453, in response to the Fall of Constantinople. Until this calamitous event, Italian humanists could travel to Byzantium and they brought back Greek texts. In 1423, Giovanni Aurispa travelled to Byzantium and returned with almost 240 manuscripts, including the first copies of Sophocles and Thucydides seen in Europe. As important as the recovery of these Greek texts was the development of new modes of literary analysis that would be employed to verify or falsify important documents in European history. It was not long, however, before humanistic literary scholars turned their attention to Christian scriptures, especially the New Testament and armed with their new skills in Greek language and composition, they set about reading the original Greek texts hoping to recover the original spirit and meaning of these early Christian texts. They argued that the Latin translation of the New Testament had corrupted the sense of the original, work that would lay the foundations of the European Reformation. The moral philosopher Lorenzo Valla (1407-1454) investigated what it was constituted 'man'. He came to the conclusion that humans always acted out of self-interest. This argument would eventually become the foundation of the Enlightenment view of humanity and form the central argument of the ideology of capitalism, individual rights, and democracy.

Civic humanists like Leonardo Bruni (1370-1444) and Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472) stressed political science and political action over everything else while the educational humanists centered their attention primarily on grammar, rhetoric, and logic. Alberti, who is more famous for his treatise on architecture as well as being a member of the Platonic Florentine Academy (1459-1522) founded by Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499), the father of Renaissance neo-Platonism, argued that the best form of government was a republic built on the Florentine model. Every citizen should be responsible for one another and should define themselves primarily in relation to the duties to their family and their city-state.

The major influence of 'humanism' on the arts was the Platonic concept of beauty. Humanism was, above everything else, an aesthetic movement. Human experience, man himself, tended to become the practical measure of all things. The ideal life was no longer a monastic escape from society, but a full participation in rich and varied human relationships. Alberti defines beauty thus:

"Such a Consent and Agreement of the Parts of a Whole in which it is found ... as Congruity, that is to say, the principal law of Nature, requires. But the Judgement which you make that a thing is beautiful does not proceed from mere opinion, but from a secret Argument and Discourse in the Mind itself."

[Leone Battista Albert, Ten Books on Architecture, trans. Leoni, London 1955]

Plato built a cosmology on Pythagoras' association of mathematics with music. Harmony was its underlying principle and, through mathematics and music, we could comprehend nature and beauty. If beauty in art was to be a reflection of beauty in nature, it too had to subscribe to the same mathematical ideas of proportion and perspective for "the same numbers that pleese the eare pleese the eie."

The 'humanist' preoccupation with Platonism finds itself alluded to in Ben Jonson's anti-masque Love's Welcome at Bolsover performed to celebrate the visit, to Bolsover Castle, of Charles I and Henrietta Maria in 1634.

"Well done, my Musicall, Arithmeticall, Geometrical gamsters! ... It is carried in number, weight and measure, as if the Airs were all Harmonie and the Figures a well-timed Proportion"

References:

Music Theory ::

- The sixteenth century saw the revival of certain aspects of ancient Greek musical practice. The application of Greek thought to music lingered behind other fields because the Greek writings on music were generally rather technical. The situation was not helped either by the lack of existing translations from the Greek into either Latin or the vernacular. The only widely available text that preserved Greek music treatises in Latin was the De institutione musica of Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius (c.480-c.525). This text played a central role in shaping the thought of Nicola Vicentino (1511-1576), the author of L'Antica Musica ridotta alla moderna prattica, first published in Rome, 1555, and reprinted in 1557, that attempted to revive the Greek musical system, reconcile it with contemporary practice, and demonstrate its applicability to contemporary composition. Vicentino adapted the three genera (diatonic, chromatic, and enharmonic) of the tetrachord to the Western musical system. Each genus consists of four notes (hence, tetrachord) spanning the interval of a perfect fourth (e.g. C-F), of which the two outside notes are fixed, and the two interior notes move according to the genus. The diatonic and chromatic genera can be accommodated within the prevailing musical system in the West; the enharmonic genus, however, requires a division of the semitone, which is normally the smallest interval in the Western system. Consequently, Vicentino devised a special keyboard instrument, the archicembalo, that used thirty-one keys for the octave (instead of the usual twelve in conventional keyboards). His motivation in reintroducing these genera was to recapture the legendary power of ancient music to affect the soul, particularly, in the modern application, through the expression of the sentiments of sung literary text. Plato and Aristotle insisted that various modes had different ethical effects. Renaissance theorists and composers mistakenly assumed that the old Greek modes were identical to the similarly-named Church modes and that the legendary powers of the former could be attributed to the latter. Vicentino seems to have been unaware of the principal ancient sources for tetrachord theory, Aristoxenus (fl 300 BC) and Ptolemy (fl 120 AD). Rather, Vicentino's account is adapted from that of Boethius Book 1 which is probably a translation of a longer treatise of Nicomachus (fl 100 AD), which has, otherwise, not survived. The influence of other works, for example, the Lucidarium (1317-18) of Marchetto of Padua, a work widely read in Italy until at least the end of the fifteenth century, (latest extant source from the sixteenth century was copied in Venice in 1509), remains to be demonstrated.

In the treatise Musica practi (1482) by Spanish-born Bartolomeo Ramis (c.14401500), which may have been influenced by earlier treatises by Al-Farabi, Ibn Sina, and Safi Al-Dinm, Ramis writes:

"The regular monochord has been subtly divided by Boethius with numbers and measure. But althought this division is useful and pleasant to theorists, to singers it is laborious and difficult to understand. And since we have promised to satisfy both, we shall give a most easy division of the regular monochord."

He then goes on to give the earliest description of a 12-note chromatic scale.

Franchino Gaffurio (1451-1522) incorporated the tuning system devised by Ptolemy into his treatises, Theorica musice (1492), Practica musice (1496) and De harmonia musicorum intrumentorum opus (1518), the most influential of the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Jonathan Walker writes:

"Ptolemy rejected both the dogma of Pythagoras and the pure subjectivism of Aristoxenus, describing the Greek genera in terms of the lowest-numbered ratios he could judge, by ear, to correspond to the intervals used by musicians; for example, he replaced the Pythagorean description of the major third (to use our term) (81:64) with the simpler ratio (5:4), which he judged to be in accordance with practice. His approach was therefore to account for practice without abandoning the precision of ratio terminology, but to use this terminology without the prescriptivism of the Pythagoreans."

By the early sixteenth century, instrumental tunings were adjusted to make thirds and sixths sound acceptable; as a result, the use of triads became more frequent, even in the final note of cadences. A sharper distinction was made between dissonance and consonance, and the masters of counterpoint invented new rules for controlling dissonance. Johannes Tinctoris (1435-c.1511), a Flemish composer at the Naples court of King Ferrante, wrote and published the Liber de Arte Contrapuncti in 1477. Heinrich Glarean or Glareanus (1488-1563), the Swiss humanist, published his Dodekachordon in 1547. In establishing his theory of twelve modes he added four new modes to the eight already adopted, and misnamed, from the Greeks. Tinctoris' rules for introducing dissonances were further refined in later treatises by other authors, including Lodovico Fogliano (?-c.1538) in Musica Theorica (1529), and Gioseffo Zarlino (1517-1590) in Le istitutioni harmoniche (1558).

Reference:

Music Printing ::

- Francisco de Peñalosa (c.1470-1528) was one of the most famous Spanish composers of his generation. His compositions were highly regarded at the time. Unfortunately for him, his music was not widely distributed; he did not benefit from the invention of printing, since he remained mostly in Spain, away from those cities, Venice and Antwerp, that would become the first centres of music printing. Later generations of Spanish composers Francisco Guerrero (1528-1599), Cristóbal de Morales (c.1500-1553), Tomás Luis de Victoria (1548-1611) who went to Italy for parts of their careers, arranged for the printing of their compositions, and as a result their compositions were as widely distributed as that of the Franco-Flemish composers who dominated music in Europe in the sixteenth century.

Johann Gutenberg perfected the art of printing from moveable type in 1450. The first printing press in Hungary was established in Buda in 1473 during the reign of Matthias Corvinus (1458-1490); a German named Andreas Hess printed the Chronica Hungarorum which he dedicated to his patron, László Karai. In the 1470s, printing was applied to monophonic music, coinciding with a new blossoming of native composition in Italy. Ottaviano de' Petrucci's anthology of chansons from ca. 1470-1500 called the Odhecaton was the first polyphonic music printed using triple impression. Michel de Toulouze had, in fact, printed at Paris, some time between 1488 and 1496, and without attribution to an author, LArt et instruction de bien dancer, the text and musical content of which are largely the same as the famous Brussels MS 9085 that is supposed to have belonged to Margaret of Austria. Petrucci, however, occupies a position analogous to Gutenburg as a printer of books, for, though Petrucci was not the first to print music or even the first to do so from movable type, he was the earliest to accomplish printing in an important way with respect to music other than plainsong. Printed music naturally gained wider circulation than manuscripts.

Using wood blocks, metal blocks or movable type, the last probably invented in Italy, early music printers had to represent a wide range of musical material whether monophonic Gregorian Chant, polyphonic music, or short musical examples in theoretical or other works. In the first known printed book that is meant to include music, the Psalterium, printed by Johann Fust and Peter Schöffer, Gutenberg's associates, at Mainz, in 1457, only the text and three black lines of the staff were printed; the fourth line was drawn by hand in red, and the notes were also written in manually. Hand-written insertions continued to be made in many liturgical works, even after the general adoption of music printing, since individual copies from large editions could thus be made to conform with local traditions.

The earliest attempt to depict actual music in print appeared in the Collectorium super Magnificat of Charlier de Gerson, produced at Esslingen in 1473 by Conrad Fyner. Here, sol, la, mi, re, ut, mentioned in the text, are represented, without staff lines, by five black squares placed in a diagonally descending row and preceded by the letter f as an F clef.

In Italy, a Roman Missale completed at Milan by Michael Zarotus of Parma on April 26, 1476, is the earliest known instance of the printing of music from movable type. Gothic-style (lozenge-shaped) notes are used; however, the printing of the music is not continued throughout. Six months later another Missale, also employing movable type but using Roman-style (square) notes, was produced by Ulrich Han (or Hahn) at Rome. In both books, double-impression printing was employed: the staves were printed in red in one impression, the plainsong notes in black in another.

Mensural note-shapes seem to have been printed for the first time in Franciscus Niger's Grammatica brevis, produced at Venice in 1480, by Theodor von Würzburg. It is not clear whether these were printed from type or from a metal block. Three note-shapes are drawn upon to illustrate five poetic meters. There are no staves, but the ascending and descending spacing of the note-heads probably indicates that melodies were intended. In 1487 there appeared, in Nicolo Burzio's Musices Opusculum, produced at Bologna by Ugo de Rugeriis, the first known, complete, printed part-composition. This was made from a wood block. It is noteworthy that printing from movable type, a more advanced technique, preceded printing from blocks.

Among the liturgical incunabula printed in Italy are several examples by Ottaviano Scotto. The presses yielded also various books on theory.

A petition, addressed by Petrucci to the Signory of Venice and dated May 25, 1498, requested the exclusive privilege for twenty years of printing music for voices, lute, and organ. Not until May 14, 1501, however, did Petrucci's first publication appear. This was the famous Harmonice Musices Odhecaton A, which is the earliest printed collection of part-music. It includes compositions by Ockeghem and Busnois, as well as by several later Franco-Flemish composers. It was followed by Canti B and Canti C, published in 1502 and 1504, respectively. Together with the Odhecaton, these form a series particularly rich in Franco-Flemish chansons. All three are in choirbook form, like most of Petrucci's later prints of secular part-music. His aim was evidently to offer "raw material," from which copies for specific performance requirements could be derived. He printed sacred music in partbook form, however, for direct practical use.

Ten out of a series of eleven Petrucci books (1504-1514) preserve a treasury of frottole (Book X is lost). The earliest piece of the type to find its way into print, however, is the Viva el gran Re Don Fernando, a barzelletta (= frottola) celebrating the Spanish conquest of Granada and rejoicing that the powerful city de la falsa fè pagana è disciolta e liberata. Probably first sung at Naples, it was included in a Roman publication of 1493 that was devoted primarily to a play commemorating the event. A few of Petruccis pieces are by Andrea Antico, who not only composed, but also worked as a type cutter, printer and publisher. In association with Giovanni Battista Columba, an engraver, and Marcello Silber (alias Franck), a printer, he produced in 1510, at Rome, his first published collection of frottole, the Canzoni nove con alcune scelte de varii libri di canto. Venice had temporarily become an unfavorable scene for artistic enterprise, owing to the serious defeat inflicted upon the republic by the League of Cambrai in 1509. However, shortly before 1520 Antico apparently returned to Venice, where he later brought out some prints in partnership with Ottaviano Scotto. In connection with works produced by partners, it is often hard to determine the exact role of each. Some printers not only did their own work, but also commissioned the printing of certain editions from other shops and printed for others as well. In 1513, Antico secured papal privileges for the printing of music and soon thereafter emerged as a serious competitor of Petrucci.

In 1525, an important advance in printing was made by Pierre Haultin of Paris (d. 1580). Whereas Petrucci had printed the staff and the notes separately, Haultin achieved one-impression type-printing: he made type-pieces in which small fragments of the staff were combined with the notes, and with these pieces the whole composite of staves and notes was built up. His method fathered, in principle, the kind of music type-printing still occasionally employed. However, it was not at once universally adopted: double printing re-emerged sporadically for more than 250 years.

Haultin's type was used by the Parisian publisher Attaingnant, among whose important publications (1528-1549) 'sacred and secular, vocal and instrumental' there are about seventy collections that contain nearly 2000 chansons (including, however, some duplications). It is significant, particularly in relation to chansons and madrigals, that Attaingnant was probably the first printer to insist on the careful placing of words under their appropriate notes. Haultin's system was applied also in the type made by Guillaume Le Bé for the famous house of Ballard that Robert Ballard together with his half-brother Adrian Le Roy established in Paris in 1551 and which would go on to print Lully in the seventeeth century and Couperin in the eighteenth and retained its privileges until the revolution of 1789.

The printing of new music was carried on side by side with attempts to preserve the best of the past. In 1537 and 1538, Hans Ott published Novum et insigne opus musicum (Nürnberg: Formschneider, 1537-1538), a two-volume anthology of 100 motets, 25 of which are attributed to Josquin des Prez. Le Roy & Ballard published Livre de meslanges (1560) in which the court poet Pierre de Ronsard justified the print's melange of old and new songs: "There is... no reason for your Majesty to be surprised if this livre de mellanges... is composed of the oldest chansons that can be found today, because the music of the old (masters) has always been considered to be the most divine, the more so, since it was composed in a century happier and less tainted by the vices which prevail in this vilest Iron Age. ...Among such men in the last six or seven score years are exalted Josquin des Prez, native of Hainaut and his disciples Mouton, Willaert, Richafort, Janequin, Maillard, Claudin, Moulu, Jaquet, Certon, Arcadelt, and at present, the more than divine Orlando....". Another innovation is attributable to the type-founder Etienne Briard (working at Avignon, ca. 1530). Instead of the square and lozenge-shaped noteheads generally used for mensural music at that time, he employed oval ones. The first printer known to have adopted this reform was Jean de Channey of Avignon, who employed Briard's type when printing Carpentras's four publications of Lamentations and other sacred music between 1532 and 1537. Important, in addition, was Jacques Moderne (known, because of his obesity, as "Grand Jacques") who founded a music house at Lyons and among whose famous publications is the Parangon des chansons (eleven books, 1538-1543). He was probably the first to print choir-books in which two voice-parts face in opposite directions on each page, to enable people sitting on either side of a table to sing from the same volume. Noteworthy, too, is Nicolas Du Chemin (ca. 1510-1576), whose issues appeared in Paris from 1540 to 1576 and included a seventeen-volume chanson collection.

Music publishing flourished also in the Low Countries, notably in Antwerp and Louvain. Tielman Susato, one of the best-known Belgian printers, established himself in Antwerp, ca. 1529, as music copyist, flutist, and trumpeter, and later as publisher. In 1543, he produced the Premier Livre des chansons à quatre parties . . . . including eight chansons by himself. Hubert Waelrant, an important composer, and the printer Jean Laet in 1554 established a publishing house, which continued to operate until Laet's death in 1597.

The collections issued by Pierre Phalèse of Louvain include both French and Flemish chansons, as well as lute music. At first a publisher employing independent printers, he undertook his own printing in 1552. After his death, his son moved the firm to Antwerp.

The reign (1515-1547) of that typically Renaissance monarch, François I, corresponds closely to the first period of the sixteenth-century chanson. Then and later the chanson drew on Italian and Netherlandish elements, spicing them with native French grace and wit. Its textual charm-of varying shades of respectability-was calculated to delight the courtiers of Fontainebleau and Paris. Despite the extremely broad humor evinced, many of the chanson composers wrote serious motets and Masses and even held positions in the Church.

The two earliest collections published by Attaingnant, apparently the first prints of polyphonic chansons, indeed the first prints of polyphonic music in France, appeared in 1528. The older one is actually dated April 4, 1527, but under a calendar in which the year began on Easter eve. Of this collection, only two parts remain. Nevertheless, its contents can be largely reconstructed from later sources in which some of the same pieces recur. The second collection survives complete but bears no date; this, however, can be approximated through circumstantial evidence.

One of the first Attaingnant collections that are not only dated but also extant in complete form is the Trente et une chansons musicales (1529). The two main composers included in it are Claudin de Sermisy, whom the music books usually name just Claudin, and Clement Janequin, to whom the entire second collection had been devoted. Despite the latter's greater fame today, and probably in his own time, we may well consider Claudin at least his equal among chanson composers of the type which, with certain differences, they both represent. These composers have been said to comprise a Paris school.

Reference:

The Renaissance and the French Court ::

- The story of the musical Renaissance at the French Royal court must be read between the lines. Scholars have long noted the absence of sources emanating from this illustrious court, as summarized by Richard Sherr:

"The French court has always been recognized as one of the major musical centers of the early sixteenth century, but

study of it is difficult; there seem to be no extant court records . . . and very few extant musical sources can be claimed

as originating in the court of the French king. However, enough can be surmised to show that composers active in court

circles were influential (perhaps even more influential than is at present believed) in creating and spreading a new style

of polyphony . . . that quickly became part of all sacred and secular genres as the sixteenth century progressed."

The dearth of sources and documentation not only hides our view of what must have been one of the

most splendid cultural centers in Europe, it also prevents us from establishing a clear concept of the

career of the most celebrated and elusive composer of the sixteenth century, Josquin Des Prez. As

scholarship increasingly points to the French court as one of the places that employed him, the frustration

at these lacunae increases. The dearth of sources for Josquin as well as for the French court forces us to

view the musical Renaissance only peripherally.

French documents and musical sources succumbed not only to the normal accidents of loss and decay,

but also to the deliberate destruction that took place during the French Revolution. Some anecdotes and

legends survive, however; some of these suggest that Josquin was a pupil of Ockeghem, that numerous

composers were pupils of Josquin, that Mouton was a colleague of Josquin, that Josquin was seen at the

French court at Lyons, that Josquin musically chided Louis XII (14981515). Poetic texts add another layer of

suggestion, listing Josquin among the composers who mourn the death of Ockeghem, the French chapels

premier member for nearly fifty years.

Reference:

Origins of Early Opera and Ballet ::

- The jongleurs of the Middle Ages moved from presenting court entertainments to organising them. They became 'dancing masters' to the nobility, teaching the steps and deportment. Many were well educated and some were descended from the Klesmorim, medieval Jewish entertainers. Domenico da Piacenza, who published the first European dance manual, De arte saltandi et choreas ducendi (1416) was the teacher of Antonio Cornazano, a nobleman by birth, who became an immensely respected minister, educator of princes, court poet, and dancing master to the Sforza family of Milan, where in about 1460 he published his Libro dell'arte del danzare. Books like these contain neither melody nor choreography, but they do detail the work of the dancing masters themselves.

Dancing served as an opportunity for lively social intercourse, as a late sixteenth-century German chronicle describes:

"After the pipers and players have been asked to play the dance, the dancer steps forward in a most elegant, polite, proud, and splendid manner, chooses a partner for whom he has a special liking among the girls and ladies present, and making his reverences, such as taking off his cap, kissing her hands, bending his knees, using friendly words and other similar ceremonies, invites her to have a lively, joyous and honest dance with him.

When she has consented to dance, they both step forward, join hands, embrace, and kiss each other (sometimes even on the mouth) and further give show of friendship with suitable words and gestures. Thereafter, when the dance itself is about to begin, they first perform the preliminary dance. This is rather solemn, and gives rise to much less improper noise and activity than the after-dance does. During the preliminary dance, those couples who are in love have a better chance to make conversation than during the after-dance, where everything is somewhat disorderly, and there is no lack of running, scrambling, pressing of hands, secret pushing, jumping, shouting, and other improper goings-on. When the dance is over, the dancer takes his partner back to her seat, and with the same reverence takes leave of her, or else stays, sitting on her lap and talking to her."

|

Many court dances had their origins outside the enclosed world of the nobility. In France the branle, a round dance of peasant origin became fashionable in the courts. Another, the morisca, or moresque, which was derived from the dances of Moorish Spain, was first mentioned in 1446. Sumptuous spectacles with mythological, symbolical or allegorical content became increasingly popular at court entertainments throughout Savoy and northern Italy. The story of Jason and the Golden Fleece featured both at the marriage of Philip the Good of Burgundy in 1430 and in the balli staged for the wedding of the Duke of Milan in 1489. European dance's most exotic influences, however, would come from Spain, which in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, was enjoying a cultural renaissance, and a mixing of its own native dances with those of Afro-American origin. For example, both the sarabande and the chaconne came from Central America sometime before 1600, but within a short time they are to be found integrated into French court dance.

Early sixteenth-century Tudor England had similar pageants, with the participants disguising after the manner of Italie. Robert Copland's Maner of Dauncynge of Bace Daunces after the Use of Fraunce (1521) as an appendix to a French grammar, demonstrates without doubt that the English were familiar with continental dance, the nobility preferring dances of a slow, measured and dignified stature, stylishly performed and modelled upon the standards of the French court, while the peasants continued their more boisterous dancing, very much as they had for centuries. Queen Elizabeth I, a skilled dancer herself, enjoyed watching the traditional English country dances, such as the jig, which came to infuse a new vitality into court dances.

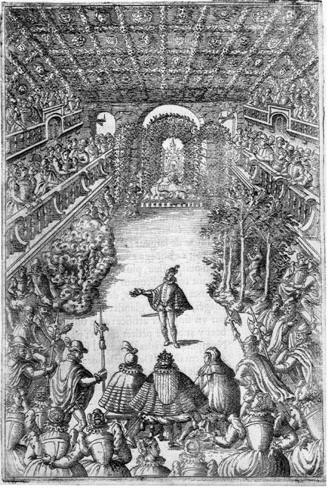

The masque developed from annual chivalrous spectacles staged by Queen Elizabeth's knights on her Accession day and from the fêtes, essentially piéces d'occasions, presented by nobility and gentry in her honour while the Court was making its summer progess. It retained many features of its predecessors including elaborate symbols expressing arcane meanings, the mingling of actors and spectators and the mask. The only known visual representation of an Elizabethan masque is to be found in the Memorial Portrait of Sir Henry Unton (c.1596). Musico-dramatic elements can be seen also in sixteenth-century suites of madrigals that were strung together to suggest a dramatic narrative. Reaching its height in the early seventeenth century, the masque became a magnificent and colourful spectacle with great emphasis placed on music and dance.

The foremost writer of the masque was Ben Jonson (1573-1637), the great dramatist, poet, and wit, with whom, for more than twenty-five years, Inigo Jones (1573-1652) would collaborate. Jones had, sometime between 1597 and 1603, traveled in Italy, probably with the brother of the 5th Earl of Rutland, where he became fluent in Italian and with the architectural ideas of Italy. An important influence was Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo (15381600) the author of Trattato dell'Arte della Pittura, Scultura et Architettura published in Milan in 1584.

As a theatrical architect, Jones became famous for his elaborate costume designs, settings, and scenic effects, which gave the masque its great popularity. Nearly 500 designs by Jones survive for costumes and scenery related to the entertainments he produced for the Stuart court between 1605 and 1640. Among the sources for Jones designs was Hieroglyphica by Giovanni Pierio Valeriano (1477-1558) first published in 1556, conceived as a manual of Egyptian and neo-Platonic hieroglyphs but which became, for the Renaissance, the lexicon of visual meaning and key to a mode of expression, thereby linking the past with the present. For Jonson and Jones' first collaboration, 'The Masque of Blackness' (1605), the costumes were drawn from Cesare Vecellio's celebrated costume book Habiti antichi et moderni di tutto il mondo (Venice, 1598). The masque was written for James I and his Queen, Anne of Denmark. The Queen and eleven other aristocratic ladies performed, wearing dress shortened to the ankle for dancing, and the staging featured elaborate lighting effects, complex stage machinery (some derived, possibly, from Book X of Vitruvius) and an artificial sea with great sea-beast and mermaids. Professional actors were, however, engaged to speak the lines. Later productions included an anti-masque performed entirely by professionals which was followed by the masque itself in which dancers in splendid costumes would descend from the stage and take partners from the audience.