What we know about early societies can be inferred only from those objects that have survived and have been recovered and identified. We cannot converse with early man and only rarely can we read what he or she had to say about him- or herself, for so much 'so-called' early literature was in fact written down many centuries after the event, an echo of an oral tradition. How we choose to infer from evidence will depend on the overarching view we hold about the way societies developed. There are two major theories of human development. The first, we might call the ecological view, says that people adapt rationally by coming up with similar solutions and responses when they find themselves facing similar environmental situations, implying maybe that the human mind is 'hard-wired' to think in particular ways. The second, a form of cultural relativism, says that the human mind is capable of a wide range of different responses, and that each society develops in a distinct, idiosyncratic way according to the accidents of a particular cultural and historical tradition. We do know, when examining early civilizations geographically isolated from one another, that each appeared to reach a certain level of development in a particular way. Despite superficial similarities, the great civilizations of South America developed languages, forms of writing, architecture and technologies distinct from those of early China, the Indus Valley or Egypt. Only where there was some form of cross-fertilization, as between Mesopotamia (the land between two rivers) and Egypt, would similarities appear. But their beliefs show that they shared certain traits. They all believed that supernatural forces animated and sustained the universe and that forms of sacrifice played a central role in the relationship between those forces and themselves. Their societies became stratified as farmers, artisans, priests, soldiers and kings defined their roles and their responsibilities to the gods, all on the basis of shared beliefs about how the universe worked. Another feature common to almost every civilization was the use they made of music for solace, celebration and entertainment.

[see also: Is Music What We Are?]Brief Timeline of History (10,000 BC to 1900 AD)

The earliest known flute, discovered in Slovenia in south-east Europe, 12-centimeter (5 inch) long, was made by Neanderthal humans 45,000 years ago. The instrument was made from the leg bone of a bear, and its original four fingerholes are intact. Its lowest note was identified as a B flat or A although beyond that the instrument is unplayable. The flute was found in a cave near the town of Nova Gorica, 65 kilometers (40 miles) west of Slovenia's capital, Ljubljana. There is some debate whether this is really a flute and we offer below some links including those that cover the debate.

Neanderthal Flute - interesting articles on the earliest known flute

Earliest music instruments found - more recent finds reported in May 2012

Music of the Neanderthals by Mary K. Miller - Feb. 21, 2000.

Doubts aired over Neanderthal Bone 'Flute' and replay by musicologist Bob Fink

German archeologists have discovered a 35,000-year-old ivory flute in a cave in the hills of southern Germany, the university of Tübingen announced Friday. The instrument, among the world's oldest and made from a woolly mammoth's ivory tusk, was assembled from 31 pieces that were found in the cave in the Swabian Jura mountains, where ivory figurines, ornaments and other musical instruments have been found in recent years. According to archeologists, humans used the area for camps in the winter and spring. The university plans to put the instrument on display in a museum in Stuttgart, according to reports.

A bird-bone flute unearthed in a German cave was carved some 35,000 years ago and is the oldest handcrafted musical instrument yet discovered, archaeologists say, offering the latest evidence that early modern humans in Europe had established a complex and creative culture. A team led by University of Tuebingen archaeologist Nicholas Conard assembled the flute from 12 pieces of griffon vulture bone scattered in a small plot of the Hohle Fels cave in southern Germany. Together, the pieces comprise a 8.6-inch (22-centimeter) instrument with five holes and a notched end. Conard said the flute was 35,000 years old.

Evidence that many of these items [musical instruments] were discovered in the Neander Valley of Germany where the very first Neanderthal fossil was discovered in 1856. A tuba made from a mastodon tusk, what looks like a bagpipe made from an animal bladder, a triangle and a xylophone made from hollowed out bone., published by Discovery magazine, was actually an April Fool hoax.

In September 22, 1999, Reuters reported the discovery of the world's oldest playable flute in China. Made about 9,000 years ago and in pristine condition, the 8.6 inch instrument has seven holes and was made from a hollow bone of a bird, the red-crowned crane. It is one of six flutes and 30 fragments recovered from the Jiahu Neolithic archaeological site in Henan province. Garman Harbottle, of the Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, New York, said, in a telephone interview, "They are the oldest playable musical instruments". In addition to suggesting that the early Chinese were accomplished musicians and craftspeople, the Jiahu site reveals that the Chinese in Jiahu had already established a village life. They had parts of the city, or village, that were devoted to different functions. Some of the other flutes, which have between five and eight holes, could also be played.

Ancient Chinese flute still plays sweet music (new link provided by Stuart Allen

A rectangular stone musical instrument, confirmed to be a type of percussion instrument used in ancient China, was recently unearthed at the site of Qijia Culture in Qinghai Province, northwest China. Archaeologists from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) and the Qinghai Provincial Archaeological Research Institute said that this is the first such instrument ever found in the history of Chinese archaeology. They said that the discovery may reverse the traditional theory that ancient percussion instruments were triangular-shaped or square. The Qijia Culture flourished in the transitional period from the Neolithic Age to the Bronze Age, some 3,500 to 4,000 years ago. Wang Renxiang, a researcher from the CASS, discovered the relic at the home of a farmer who lives in the Lajia village, where the ruins of the Qijia Culture are located. The finely-cut and well-polished instrument, 96 cm long and 66 cm wide, is dark blue and still produces a loud, clear sound. A number of jade articles used in primitive religious rituals were found at the site, as well as a city moat which, experts said, is dozens of metres wide and five metres deep.

[taken from: 4000 year-old percussion instrument unearthed]Tunes were rung on handbells in China over 5000 years ago, although western civilisation has long associated the sound of larger bells with the Christian Church. Many religions around the world make use of bells in their worship. Bells of many shapes and sizes have been used to ring out glad tidings, toll for the departed and to call the faithful to worship. The British Isles have long been known as the "Ringing Isles" and in the eighteenth century, the composer Handel cited the bell as the English National Instrument. Tower bell ringers started the art of "ringing the changes" as long ago as the sixteenth century. This change ringing, practised in the frequently cold belfry, brought about a suggestion, according to some history books, "Why don't you create some small bells which you can hold in your hand and take to the local inn to practise in warmth and comfort?"

4500 BC

Oldest known bell found near Babylon.

4000 BC

The first recorded use of handbells in China.

640

'Campaniles' or 'bell towers' are built throughout Europe. Campaniles were used to ring warnings of Battles, important civic events, and of course, Church services.

710

Bells are made from a mixture of alloys creating the familiar bronze bell which exists today. For the first time, bells can be created to have a specific tone or pitch.

1173

Construction begin on the "campanile" in the Italian City of Piza. Unfortunately, it is built on unstable ground and is unsuitable as a bell tower.

1495

The art of changing ringing begins. The creation of music based on ever changing sequential patterns of sound on multiple bells.

1707 The first handbells are created to train change ringers.

1758

Handbell ringers experiment with new forms of music.

1847

P.T. Barnum hires 'Swiss Bell Ringers' to be part of his circus.

The earliest historical records relating to bronze drums appeared in the Shi Ben, a Chinese book dating from at least the third century BC. This book is no longer extant; however a small portion of it appears in another classic, the Tongdian by Du You. The Hou Han Shu, a Chinese chronicle of the late Han period compiled in the fifth century AD, describes how the Han dynasty general, Ma Yuan (14 BC-49 AD) , collected bronze drums from Jiaozhi (northern Vietnam) to melt down and then recast into bronze horses. From that point on, many official and unofficial Chinese historical records contain references to bronze drums. In Vietnam, two fourteenth-century literary works written in Chinese by Vietnamese scholars, the Viet Dien U Linh and the Linh Nam Chich Quai record many legends about bronze drums. Later works such as the Dai Viet Su Ky Toan Thu, a historical work written in the fifteenth century, and the Dai Nam Nhat Thong Chi, a book about the historical geography of Vietnam compiled in the late nineteenth century, also mention bronze drums. Additionally, a wooden tablet found in Vietnam dating from the early nineteenth century describes the discovery of some bronze drums.

[taken from: The Present Echoes of the Ancient Bronze Drum: Nationalism and Archeology in Modern Vietnam and China by Han Xiaorong]Chinese music is as old as Chinese civilization. Instruments excavated from sites of the Shang dynasty (circa 1766-c. 1027 BC) include stone chimes, bronze bells, panpipes, and the sheng. The ancient Chinese wind instrument, the cheng, sheng or Chinese organ, consisting of a set of pipes arranged in a hollow gourd and sounded by means of free-reeds, the air being fed to the pipes in the reservoir by the mouth through a pipe shaped like the spout of a tea-pot.

Music flourished during the Shang dynasty (1523-1027 BC) but the intellectual foundation of the Chinese musical system grew out of early advances in Chinese philosophy and mathematics. For the Chinese the understanding of the meaning of existence, a quest central to cultures from all ages and places, focused on (1) inter-personal communication and its contribution to society as a whole, and (2) the human position in the cosmos. Their cosmic view, based on a universal resonance and harmony, informed the Chinese system of harmonic intervals. Acoustical systems were seen to mirror the physical universe; the study of one led to a deeper understanding of the other. The Chinese were among the first to consider tuning systems and temperament, using acoustical physics and mathematics. Chinese musicians using silk strings were the first to employ scales based on equal temperament.

In the Zhou dynasty (circa 1027-256 BC) music was one of the four subjects that the sons of noblemen and princes were required to study, and the office of music at one time comprised more than 1400 people. Although much of the repertoire has been lost, some old Chinese ritual music (yayue) is preserved in manuscripts.

- In Chinese music theory, which dates back to the fifth century BC but would later influence the theory of music in Japan, the five notes of the musical scale (called a pentatonic scale) were intimately related to all the other 'fives' based on the five material agents: the directions, the seasons, organs, animals, etc. The five material agents were a sophisticated theory of change: all change, including musical change, was governed by the relationship of the five material agents either as they engendered one another or conquered one another. These two possible relationships, the sequence of the five material agents as the either engender or conquer one another, in part governed the sequence of notes in the scale.

Wood Fire Earth Metal Water chiao (3rd note) cheng (4th note) kung (1st note) shang (2nd note) yü (5th note) In addition, the five material agents were collapsed in a larger notion of yang and yin, the male (creation) and female (completion) principles of change in the universe. Likewise, the pentatonic scale was divided into a male scale and a female scale, or ryo and ritsu in Japanese. The most important note in the pentatonic scale is the third note of the scale, called the 'cornerstone'. Corresponding with the five material agents, the "cornerstone" is related to the 'Wood agent' and therefore also to 'Spring' and to the 'East', or beginnings, and jen , or 'benevolence, humaneness', the most important of the virtues). While in the West we define tonal scales based on the first note of the scale (called the 'tonic'), in Chinese and Japanese music, the scale is defined by the 'cornerstone', or third note. If the relationship between the first note (kung, which corresponds to the 'Earth agent' and the 'centre') of the scale and the 'cornerstone' form a perfect third (if you play middle C and E on a piano, you're playing a perfect third), the scale is male; if these two notes form a perfect fourth (middle C and F on a piano), the scale is female.

Chinese and Japanese musical theories were based on the eight categories of sound (called, in Chinese, pa yin): metal (bells), stone (stone chimes), earth (ocarina), leather (drums), silk (stringed instruments), wood (double-reed wind instruments), gourd (sho, or mouth organ), and bamboo (flute).

[taken from: Early Japanese Music by Richard Hooker]

During the Qin dynasty (221-206 BC) music was denounced as a wasteful pastime; almost all musical books, instruments, and manuscripts were ordered to be destroyed. Despite this severe setback Chinese music experienced a renaissance during the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220), when a special bureau of music was established to take charge of ceremonial music. During the reign (AD 58-75) of Ming-Ti, the Han palace had three orchestras formed from 829 performers. One orchestra was used for religious ceremonies, another for royal archery contests and the third for entertaining the royal banquets and the harem.

The tolerance of the T'ang Imperial Court to outside influence and the free movement along the East-West trade route known as the Silk Road, saw major urban centres become thriving cosmopolitan cities with the Chinese capital, Chang'an (modern Xian) expanding to reach a population of over one million. During the T'ang dynasty (618-906) Chinese secular music (suyue) reached its peak. Emperor T'ai-Tsunghad ten different orchestras, eight of which were made up of members of various foreign tribes; all the royal performers and dancers appeared in their native costumes. The imperial court also had a huge outdoor band of nearly 1400 performers. Musicians from the West were regular features in the major cities and introduced new instruments and music styles. The T'ang emperor Xuanzong (712755) was a great lover of the new Western music that was played regularly at court along with traditional Chinese music and instruments such as bells and zithers.

By the late T'ang and the Song period (960-1279 AD) the cosmic philosophical viewpoint had disintegrated. The Song period, in particular, spelled disaster for ancient musical aesthetics as China experienced serious political retreat.

Chinese cultural achievements from these early periods entered the cultural life of those countries bordering or engaged in contact with China, i.e. Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asia. The origins of Japanese music begin at around 3000 BC during the Jomon Culture, when, according to evidence found at archeological digs, music was first used in ceremonies. The primitive instruments included stone whistles, bronze bells, barrel drums, zithers, and croatal bells. The first music apparently directly a result of migration from China and Korea, was passed down from the ancient Ainu of Japan, and became the dominant secular musical style of ancient Japan, gigaku or Kure-gaku. This style is associated with the popular dances and pantomimes of southern China and northern Indochina. It was, as far as we know, the most popular 'official' music in late sixth-century Japan.

Both Togaku and To-sangaku were musical styles derived from T'ang China. The musical life of the T'ang court obeyed a formal set of rules, called the Ten Styles of Music which governed the hierarchy and use of Chinese and foreign musical styles in the T'ang court. When musical performances followed these academic rules and types, it was known asTogaku, or T'ang music. When, however, the music consisted of popular music from T'ang China, this music was classified as To-sangaku, or unofficial T'ang music. Sangaku was the most popular and exciting of these early music types, where songs were interspersed between acrobatics and energetic pantomimes.

Finally, Koma-gaku was the music of the three Korean kingdoms and Rinyu-gaku was the music of Southern Asia. The latter always involved dances and pantomimes.

- In Chinese music theory, which dates back to the fifth century BC but would later influence the theory of music in Japan, the five notes of the musical scale (called a pentatonic scale) were intimately related to all the other 'fives' based on the five material agents: the directions, the seasons, organs, animals, etc. The five material agents were a sophisticated theory of change: all change, including musical change, was governed by the relationship of the five material agents either as they engendered one another or conquered one another. These two possible relationships, the sequence of the five material agents as the either engender or conquer one another, in part governed the sequence of notes in the scale.

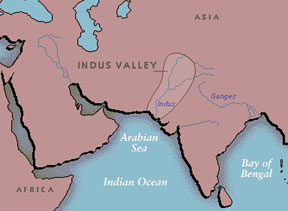

The Indus Valley civilization, the largest of the four ancient civilizations, flourished around 2,500 B.C. in the western part of South Asia, in what today is Pakistan and western India. It is often referred to as Harappan civilization after Harappa, the first city discovered in the 1920's. Most of the civilization's ruins, including other major cities, remain to be excavated. Its script has not been deciphered and basic questions about the people who created this highly complex culture are unanswered. However, there is some evidence that it had a musical tradition some of which survives to this day amongst the Dravid people of southern India and Sri Lanka.

Ahmad Hassan Dani comments: "There is one particular aspect which does survive, not only in South India, but also in Sri Lanka. This came to my mind when the year before last I was in Sri Lanka at the time of their general election and they had a music performance. In the music performance they were having the dance, and with their drum or dholak, and it at once reminded me of my early life, for I was born in Central India, and I had seen this kind of dance. Not with tabla, tabla is a later comer in our country. It at once reminded me that we have got this dholak in the Indus Valley Civilization. I don't know about the dance, but at least the dholak we know. We have not stringed instruments in Indus Valley Civilization. We have got the flute, we have got cymbals, we have got the dholak. Exactly the same musical instruments are played today in Sri Lanka and South India. So I would like to correct myself: to say that nothing is surviving in South India [is wrong]; this is the only instrument which is surviving there according to me from the Indus Civilization."

From The Indus Script - Ahmad Hassan Dani interviewed by Omar Khan on January 6, 1998

The Uruk Lute: Elements of Metrology by Richard Dumbrill

"Earlier this year I examined a cylinder seal acquired by Dr Dominique Collon on behalf of the British Museum. The piece is now listed as BM WA 1996-10-2,1, and depicts, among others, the figure of a crouched female lutanist. The seal, which I shall not discuss here, has been identified by Dr Collon as an Uruk example and thus predates the previously oldest known iconographic representations by about 800 years. Little can be said about the instrument except that it would have measured about 80 centimetres long and that some protuberances at the top of its neck might be the representation of some device for the tuning of its strings. Otherwise, the angle of the neck in its playing position as well as the position of the musicians arms and hands is consistant with one of the aforementioned Akkadian seals, namely BM 89096. This shows that the instrument evolved very little for the best part of one millennium, for the probable reason that it already had completed its development, as early as the Uruk period.

The existence of the lute among the instrumentarium of the late fourth millennium [BC] is of paramount importance as it is consequential to the understanding and usage of ratios at that period. I am further willing to hypothesize that the lute might have been at the origins of the proportional system. This is what I shall now demonstrate.

The lute differs from the two other types of stringed instuments, namely harps and lyres, in that each one of their strings produces more than one sound. This peculiarity qualifies the lute as a fretted instrument, not on the basis that it is provided with frets as we know them on the modern guitar, for instance, but in that each of the different notes generated from each of its strings is determined by accurate positions marked on the neck of the instrument. These are defined from the principle of ratios, and it is the principle of the stopping of the strings along the neck of the instrument that was at the origins of the understanding of such ratios."

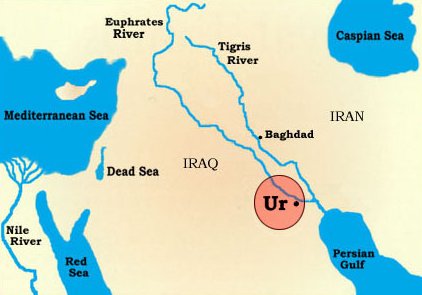

Note: Uruk or Erech was an ancient Sumerian city of Mesopotamia, on the Euphrates and NW of Ur (in present-day Southern Iraq). It is the modern Tall al Warka. Uruk, dating from the 5th millennium BC, was the largest city in Southern Mesopotamia and an important religious center. The sanctuaries of the goddess Inanna (who corresponds to the Babylonian Ishtar and is also called Nana or Eanna) and Anu, the sky god, date from the early 4th millennium BC The temple of Anu, known as the white temple, stood on a terrace and seems to have been a primitive form of ziggurat. Uruk was the home of Gilgamesh, it's legendary king, and is mentioned in the Bible (Gen. 10.10). There have been excavations at the site since 1912.

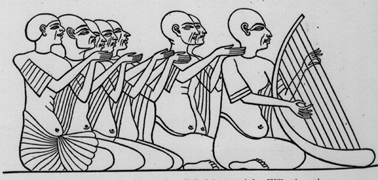

Iconographic evidence from about 3000 BC indicates that double-reed wind instruments were in use in Mesopotamia. The Gold Lyre of Ur, c. 2650 BC, was one of a number of musical instruments discovered in royal burial sites which help illustrate the prominent role music played in Sumerian life and religion. Musicians and their instruments appear frequently in the artwork and archeological artifacts of Iraq's deep antiquity.

While the exact music from ancient Mesopotamia can never be recovered, Iraq has produced intruiging written evidence supporting the existence of sophisticated music theory and practice in Sumerian, Babylonian and Akkadian cultures. A family of musical texts inscribed in cuneiform tablets reveal a wealth of musical information about specific tuning modes, string names and hymns. These written documents demonstrate that musical activity was being recorded a thousand years prior to the rise of ancient Greek civilization, a culture commonly credited with the earliest development of musical documents.

[taken from: The Sumerian Gold Lyre by Douglas Irvine]The religion of the ancient Sumerians has left its mark on the entire middle east. Not only are its temples and ziggurats scattered about the region, but the literature, cosmogony and rituals influenced their neighbours to such an extent that we can see echoes of Sumer in the Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition today. From these ancient temples, and to a greater extent, through cuneiform writings of hymns, myths, lamentations, and incantations, archaeologists and mythographers afford the modern reader a glimpse into the religious world of the Sumerians. Each city housed a temple that was the seat of a major god in the Sumerian pantheon, as the gods controlled the powerful forces which often dictated a human's fate. The city leaders had a duty to please the town's patron deity, not only for the good will of that god or goddess, but also for the good will of the other deities in the council of gods. The priesthood initially held this role, and even after secular kings ascended to power, the clergy still held great authority through the interpretation of omens and dreams. Many of the secular kings claimed divine right; Sargon of Agade, for example, claimed to have been chosen by Ishtar/Inanna. The rectangular central shrine of the temple, known as a 'cella,' had a brick altar or offering table in front of a statue of the temple's deity. The cella was lined on its long ends by many rooms for priests and priestesses. These mud-brick buildings were decorated with cone geometrical mosaics, and the occasional fresco with human and animal figures. These temple complexes eventually evolved into towering ziggurats. The temple was staffed by priests, priestesses, musicians, singers, castrates and hierodules. Various public rituals, food sacrifices, and libations took place there on a daily basis. There were monthly feasts and annual, New Year celebrations. During the later, the king would be married to Inanna as the resurrected fertility god Dumuzi, whose exploits are dealt with below.

[taken from: Sumerian Mythology - FAQ]Mesopotamia - a general survey

Sumerian Golden Lyre - home page

The history of musical development in Iran [Persia] dates back to the prehistoric era. The great legendary king, Jamshid, is credited with the invention of music. Fragmentary documents from various periods of the country's history establish that the ancient Persians possessed an elaborate musical culture. The Sassanian period (A.D. 226-651), in particular, has left us ample evidence pointing to the existence of a lively musical life in Persia. The names of some important musicians such as Barbod, Nakissa and Ramtin, and titles of some of their works have survived. With the advent of Islam in the seventh century AD. Persian music, as well as other Persian cultural traints, became the main formative element in what has, ever since, been known as "Islamic civilization. Persian musicians and musicologists overwhelmingly dominated the musical life of the Eastern Moslem Empire. Farabi (d. 950), Ebne Sina (d. 1037), Razi (d. 1209), Ormavi (d. 1294), Shirazi (d. 1310), and Maraqi (d. 1432) are but a few among the array of outstanding Persian musical scholars in the early Islamic period. In the sixteenth century, a new "golden age" of Persian civilization dawned under the rule of the Safavid dynasty (1499-1746).

[taken from: An Introduction to Persian Music by Professor Hormoz Farhat]Ugarit, not far from modern-day Beruit, flourished from the fourteenth century BC until 1200 BC, when it was destroyed. Its language is similar to Phoenician. The city was rediscovered in 1928 by a peasant whose plow uncovered a ancient tomb near Ras Shamrah in northern Syria. A group of French archaeologists led by Claude F.A. Schaeffer started excavating the city in 1929.

Of particular importance to music history was the discovery of a terracotta tablet which includes a musical staff and which has been dated to about 1400 BC and is now housed at the National Museum, Damascus. This, the oldest known musical staff, is written on the lower part of the tablet below the double line, while the words to a hymn referring to the gods appear on the upper part. This is therefore a complete text, with both words and music.

Duchesne-Guillemin was one of the early investigators of the reconstruction of ancient Babylonian musical scales and music theory. She was the first scholar to explore and explain the musicological significance of the sequence of number-pairs of musical strings in a cuneiform text of the first millennium B.C.E. excavated at the archaeological site of Nippur in southern Iraq. She was able to demonstrate that the tablet presented two series of intervals on a musical scale; that musical intervals of fifths, fourths, thirds, and sixths were known at that time; and that the evidence for an ancient Mesopotamian heptatonic-diatonic scale was strong. She was also one of the few scholars who attempted to interpret the musical instructions found on a cuneiform tablet (mid-2nd millennium B.C.E.) from ancient Ugarit in Syria which contained a nearly complete hymn written in the Hurrian language but whose musical instructions were in semitic Akkadian.

Evidence of Harmony in Ancient Music by Robert Fink

Music of the Ancient Near East by Stefan Hagel

Trumpets in the Bible were of a great variety of forms, and were made of various materials. Some were made of silver (Num. 10:2), and were used only by the priests in announcing the approach of festivals and in giving signals of war. Some were also made of rams' horns (Josh. 6:8). They were blown at special festivals, and to herald the arrival of special seasons (Lev. 23:24; 25:9; 1 Chr. 15:24; 2 Chr. 29:27; Ps. 81:3; 98:6). This type of trumpet, the shofar is still blown today in Jewish services on Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year).

Our understanding of the role of music in the life of Ancient Egypt is enriched immeasurably by the pictorial evidence that has survived in paintings and carvings. The wall paintings from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun, an obscure accountant attached to the Temple of Amun in Thebes (present-day Karnak) who died around 1350 BC, include three female musicians who are shown clapping in time to the music of a flute played by a fourth musician, with the words of their song spelled out in a hieroglyphic speech bubble above their heads. Two of the seated musicians are shown not in profile, as one might expect in Egyptian art, but full face. The artist felt able to break the rules because the women he was depicting were foreign and of low status.

The musicologist Rafael Pérez Arroyo, former director of Sony Hispánica collection, has released the first fruit of his many years of research into the music of Ancient Egypt. The result is a spectacular and luxuriously edited book of some 500 pages entitled Music in the Age of Pyramids. As Todd McComb points out ".... Arroyo composed this music himself. It is not based upon surviving notation. His study has obviously been very extensive however: metric structure of hymns which survive in writing, whatever discussion of music theory he could find, sonic descriptions by ancient authors, iconography, etc.. He believes he has detected a partial chironomy (hand gestures, the same source claimed for Biblical music), and discovered three basic modes for Ancient Egyptian music. This leaves the sense that some 'shell' of Ancient Egyptian music has been unearthed, but no real music. Arroyo establishes a pentatonic basis, and sometimes uses Coptic hymns for the music. Arroyo also makes many claims regarding Ancient Egypt's musical influence on other cultures. While his correlations with known symbology in for example Indian & China are certainly worth considering, I personally find his claims to causality to be over-stretching."

Music and Dance in Ancient Egypt

Early Harp History - including its use in Ancient Egypt

The earliest evidence of musical activities in Denmark are the large, twisting bronze horns dating from the Bronze Age (1500-500 BC). Soon after the first examples (three pairs) were found in a bog in 1797, the name lur was attached to them. 61 lurs have been found (the most recent in 1988) in southern Scandinavia and the Baltic area, most of them in Denmark (38). They tend to be found in pairs, but it is uncertain what they were used for. The same applies to the two golden horns found in Gallehus, which some people have interpreted as musical instruments.

[taken from: Denmark - Culture - History]Professor Peter Holmes of London believes that the first Bronze horns could have been cast in the North East of Ireland about 1500 B.C. These were quite small, relatively heavy and not highly decorated. Gradually as the culture surrounding them spread South through the Island, so too the casting expertise improved until the youngest instruments were made in the South West around 800 B.C. Because of this gradual evolvement, a wide variety of shape, design and size of horn were made. It appears that certain particular designs and tuning were indicative of the area where an instrument was made. Because a large number of originals survive it is likely that there were many horns played throughout Ireland in the Late Bronze Age. As a fragment was found in West Scotland and a drawing comes from Sussex in England it is also quite possible that a sibling culture existed there and there was most likely interaction between the two Islands.

The bells or Crothall (rattles) present a different mystery as all 48 were found in the 1820s at one particular site in the Irish Midlands. This may suggest that they were assembled from around the country for burial or equally, they may have been a feature of that particular area. Crothalls can either be shaken hard and fast between the two hands to produce complex rhythms or let hang by the attached ring and made to gently chime.

Though there is still much to be learned about the Bronze Age in Ireland, intensive studies have been published by Prof. George Eoghan, Prof. Peter Holmes and others on the vast amounts of jewelry, sacred horns, tools, weapons, cauldrons and remains of habitation that survive. These point to a rich and varied culture with high levels of population and probably a common religion and economy. Curiously, following the end of the Bronze Age around 650 BC there seems to have been a form of Dark Age as virtually no artifacts or remains come down to us from the following three hundred years around 300 BC.

We come into the Iron Age with a completely different set of influences which stem mainly from Celtic Switzerland. This era which lasted through to and beyond the introduction of Christianity in 432 AD is also believed to be the source of many of the great myths and legends of Ireland that survive today, though it is quite possible that some of the older stories may come from the earlier Bronze Age. It is important to point out that the major part of Irish Pre-history was not Celtic in origin. For over six thousand years the earlier or original Irish developed and practiced a unique culture.

They created decorative jewelry of great beauty. Their weapons were fine and deadly. An entire technology was developed around the earliest examples of bronze welding. Discoveries of artifacts from other cultures in Ireland and Irish objects abroad prove the Irish traders traveled throughout Europe, North Africa and the Middle East during the Stone and Bronze Ages.

It is therefore a misnomer to refer to the people of Ireland as Celtic. To do this is to deny more than two thirds of Irish Pre-history and history. Today it is generally accepted that the closest descendants of ancient Ireland live in Connamara in the West of Ireland. Here the people could be referred to as Aboriginal or Native. Through their distinctive Irish language and long tradition of music and song they keep alive much of Ireland's long and powerful story.

[taken from: The History of Bronze Age Horns]Livy vividly depicts the noise accompanying the Gaul's mad rush into battle. Describing the battle of the river Allia (387 or 380 BC), he says:

".. they are given to wild outbursts and they fill the air with hideous songs and varied shouts.' Of the Gauls in Asia he writes: 'their songs as they go into battle, their yells and leapings, and the dreadful noise of arms as they beat their shields in some ancestral custom - all this is done with one purpose, to terrify their enemies."Celts fought at the battle of Telamon in 225 BC.

"The Celts had drawn up the Gaesatae from the Alps to face their enemies on the rear ... and behind them the Insubres .... The Insubres and the Boii wore trousers and light cloaks, but the Gaesatae in their overconfidence had thrown these aside and stood in front of the whole army naked, with nothing but their arms; for they thought that thus they would be more efficient, since some of the ground was overgrown with thorns which would catch on their clothes and impede the use of their weapons. On the other hand the fine order and the noise of the Celtic host terrified the Romans; for there were countless trumpeters and horn blowers and since the whole army was shouting its war cries at the same time there was such a confused sound that the noise seemed to come not only from the trumpeters and the soldiers but also from the countryside which was joining in the echo."

Little written music has been found from this ancient time, and we have no recordings from thousands of years ago, so people today do not know what the music of ancient Greece sounded like. Because ancient Greeks wrote about their music and music theory, we know something about them. The ancient Greeks are remembered for creating special arrangements of tones we now call the Greek modes. They were used later in religious music in Europe, and have been the basis of much Western music for centuries. The uneven meters that are still popular in Greek music date back to ancient times when Greek poetry was read in a special, rhythmical way. Instead of music notation looking like it does today, ancient Greek music notation used letters of the alphabet. When there was music and text, the alphabet-style music notation appeared above the words. There is an example of this early notation carved in stone from the second century BC, in the Archaeological Museum in Delphi, Greece. It is a hymn sung to the Greek god Apollo.

[taken from: Greek Music by Silver Burdett]Music was essential to the pattern and texture of Greek life, as it was an important feature of religious festivals, marriage and funeral rites, and banquet gatherings. Our knowledge of ancient Greek music comes from actual fragments of musical scores, literary references, and the remains of musical instruments. Although extant musical scores are rare, incomplete, and of relatively late date, abundant literary references shed light on the practice of music, its social functions, and its perceived aesthetic qualities. Likewise, inscriptions provide information about the economics and institutional organization of professional musicians, recording such things as prizes awarded and fees paid for services. The archaeological record attests to monuments erected in honor of accomplished musicians and to splendid roofed concert halls. In Athens during the second half of the fifth century BC, the Odeion (roofed concert hall) of Perikles was erected on the south slope of the Athenian akropolisphysical testimony to the importance of music in Athenian culture.

In addition to the physical remains of musical instruments in a number of archaeological contexts, depictions of musicians and musical events in vase painting and sculpture provide valuable information about the kinds of instruments that were preferred and how they were actually played. Although the ancient Greeks were familiar with many kinds of instruments, three in particular were favored for composition and performance: the kithara, a plucked string instrument; the lyre, also a string instrument; and the aulos, a double-reed instrument. Most Greek men trained to play an instrument competently, and to sing and perform choral dances. Instrumental music or the singing of a hymn regularly accompanied everyday activities and formal acts of worship. Shepherds piped to their flocks, oarsmen and infantry kept time to music, and women made music at home. The art of singing to one's own stringed accompaniment was highly developed. Greek philosophers saw a relationship between music and mathematics, envisioning music as a paradigm of harmonious order reflecting the cosmos and the human soul.

[taken from: Music in Ancient Greece]We summarise John Curtis Franklin's thesis entitled The Invention of Music in the Orientalizing Period but include also his more recent thoughts on the subject.

The legend that Terpander rejected "four voiced song" in favor of new songs on the seven-stringed lyre (fragment 4 Gostoli) suggested initially that an encounter between two musical traditions, which may have taken place during the Greek Orientalizing period (c. 750-650 BC), was catalyzed by the westward expansion of the Assyrian empire. The seven-stringed lyre answers clearly to the heptatony which was widely practiced in the ancient Near East, as known from the diatonic tuning system documented in the cuneiform musical tablets. However, while the Greek evidence preserves vestiges of the Old Babylonian (< Ur Dynastic III, Sumerian) version of diatonic music with its practical and theoretical emphasis on a central string. I am no longer certain that the system's transmission took place in the Orientalizing Period; I am now convinced that the seven-stringed lyre survived in Cyprus and those areas of the Aegean where Bronze Age Achaean culture persisted, such as Athens, Euboea, Lesbos, Arcadia, Crete, Smyrna. "Four voiced song" must be understood as describing the inherited melodic practice of the Greek epic singer. The syncretism of these two traditions may be deduced from the later Greek theorists and musicographers. Though diatonic scales were also known in Greece, even the late theorists remembered that pride of place was given to other forms of heptatony the chromatic and enharmonic genera, tone structures which cannot be established solely through the resonant intervals of the diatonic method. Nevertheless, these tunings were consistently seen as modifications of the diatonic which Aristoxenus believed to be the "oldest and most natural" of the genera and were required to conform to minimum conditions of diatony. Thus the Greek tone structures represent the overlay of native musical inflections on a borrowed diatonic substrate, and the creation of a distinctly Hellenized form of heptatonic music. More specific points of contact are found in the string nomenclatures, which in both traditions are arranged to emphasize a central string. There is extensive Greek evidence relating this "epicentric" structure to musical function, with the middle string a sort of tonal center of constant pitch, while the other strings could change from tuning to tuning. So too, in the Mesopotamian system; the central string remained constant throughout the diatonic tuning cycle. The question that remains is whether the Mesopotamian approach to diatony was known in the Minoan and Mycenaean palaces, as the Ugaritic evidence might suggest, or whether it revitalized a Bronze Age Aegean tradition during the Orientalizing period, via Phoenician or Neo-Assyrian influence, as Cypriot and Lydian evidence might suggest.

In a manner analogous to the way the Greeks took up ideas of music from the ancient Near East, so the Romans inherited many of their ideas about music and their use of musical instruments from the Greeks. This much is confirmed by writings surviving from the period and from the fragments and icongraphic evidence we have of the instruments themselves. Because, so far as we know, the Romans had no organised form of musical notation we have no idea what music they played. Modern 'reconstructions' of music to accompany 'Roman' events must be considered wholly conjectural. We do know that in the Greek and Roman civilizations double-reed instruments were highly regarded. Playing the aulos or tibia was associated with high social standing and the musicians enjoyed great popularity and many privileges. Portrayals of aulos players in Ancient Greece traditionally depict a musician blowing two instruments; this proves that the aulos was a double instrument. Different types of aulos were played on different occasions - as was the Roman tibia - for example, in the theatre, where it accompanied the chorus. So, whether in religious ceremonies, public performance, private functions or on the battlefield, music, indisputably, played an important role in the lives of both the Greeks and the Romans.

Ktesibios (Ctesibios) of Alexandria who lived between 300-230 BC, invented the hydraulus, in which water pressure was used to stabilize the wind supply. The pipes were arranged in rows upon the wind chest and the air was permitted to enter any pipe at will by means of wooden sliders. The hydraulus was the prevailing organ for several centuries and reappeared at intervals throughout the Middle Ages.

Ancient Greek Music - a bibliography

Hydraulus - a history and description

Greek and Latin Music Theory - 10 volumes published by the University of Nebraska Press until 2004

The leaders of the early Christian Church, guided by Old Testament precedent and New Testament admonition (e.g. Colossians iii.16 and James v.13), gave their general approval to the use of music in the services of the church; but although Christianity was a Jewish sect at its inception and therefore heir to the musical materials and practices of Judaism, it possessed during its earliest period neither the financial resources nor, since it was forced by persecution to conceal its activities, the physical facilities necessary for the development of a tradition of choir singing like that of the Jews. As a result of these circumstances the singing that flourished among the early Christians was largely congregational. Specific practices varied from place to place, but the activity of singing praise was common to Christians everywhere. 'The Greeks use Greek', reported Origen (b. 185 - d. 253 or 254), 'the Romans Latin ... and everyone prays and sings praises to God as best he can in his mother tongue'. The singing of Old Testament psalms was practiced, initially at least, by Christians of both sexes and of all ages, but some of the later church Fathers, heeding the interdiction of St. Paul (1 Corinthians xiv.34), opposed the participation of women in congregational singing.

Not only were the psalms themselves borrowed by the Christians from their Jewish predecessors but Jewish methods of performance were also incorporated into Christian worship. References to antiphonal and responsorial singing occur in the works of several patristic writers. Eusebius (b. about 260 - d. before 341), Bishop of Caesarea, in whose Historia ecclesiastica Philo's account of antiphony among the Therapeutae is quoted, remarked that in his own time the manner of singing described by Philo was still practiced among the Christians. Responsorial psalmody was mentioned, probably with reference to Rome, by Tertullian (born c. 160 AD). Antiphonal and responsorial singing may have appeared first among those Christians in closest geographical proximity to the Judaic roots of Christianity, but by the end of the fourth century at the latest these methods of performance were common to Eastern and Western churches alike. Moreover, antiphonal and responsorial singing were not used exclusively in connection with psalm texts but were applied to other types of texts as well, and exercised an influence on the development of the early Christian liturgy. Patristic opinion was divided concerning the propriety of using instruments to accompany singing. Because of their association with pagan festivities, instruments were censured by many of the church Fathers, among them Clement of Alexandria (died c. 215 AD), who forbade their use in church. Even as late a writer as Didymus of Alexandria (died 396 AD), however, defined a psalm as 'a hymn which is sung to the instrument called either psaltery or cithara'.

[taken from: Influence of the Ancient JewishTemple and Synagogue Tradition on Early Christian Music and Liturgy]Music in the Early Christian Church - a summary

During its thousand-year history the Byzantine Empire outfought, out-maneuvered, or simply outlasted successive waves of enemies who attacked it from all four points of the compass. The remarkably varied peoples who made up the Byzantine Empire created a distinctive and vibrant civilization where art and learning flourished when most of Western Europe was still literally mired in the Dark Ages. And although the Byzantine Empire as a political entity was finally extinguished in the mid-fifteenth century, it survived long enough to transmit to the West the great literary works of classical antiquity that helped inspire the Italian Renaissance. Byzantine music is the medieval sacred chant of Christian Churches following the Orthodox rite. This tradition, encompassing the Greek-speaking world, developed in Byzantium from the establishment of its capital, Constantinople, in 330 until its fall in 1453. It is undeniably of composite origin, drawing on the artistic and technical productions of the classical age, on Jewish music, and inspired by the monophonic vocal music that evolved in the early Christian cities of Alexandria, Antioch and Epheus.

Byzantine chant manuscripts date from the ninth century, while lectionaries of biblical readings in Ekphonetic Notation (a primitive graphic system designed to indicate the manner of reciting lessons from Scripture) begin about a century earlier and continue in use until the twelfth or thirteenth century. Our knowledge of the older period is derived from Church service books Typika, patristic writings and medieval histories. Scattered examples of hymn texts from the early centuries of Greek Christianity still exist. Some of these employ the metrical schemes of classical Greek poetry; but the change of pronunciation had rendered those meters largely meaningless, and, except when classical forms were imitated, Byzantine hymns of the following centuries are prose-poetry, unrhymed verses of irregular length and accentual patterns. The common term for a short hymn of one stanza, or one of a series of stanzas, is troparion (this may carry the further connotation of a hymn interpolated between psalm verses). A famous example, whose existence is attested as early as the fourth century, is the Vesper hymn, Phos Hilaron, "Gladsome Light"; another, O Monogenes Yios, "Only Begotten Son," ascribed to Justinian I (527-565), figures in the introductory portion of the Divine Liturgy. Perhaps the earliest set of troparia of known authorship are those of the monk Auxentios (first half of the fifth century), attested in his biography but not preserved in any later Byzantine order of service.

[partly taken from: Orthodox Byzantine Music]Origen's observation that the practices of early Christians reflected their cultural origins found its most remarkable example in the early Coptic church. The Coptic Kyrie is related to ancient Egyptian traditions for the sun-god. Scholars have found that the Antiphonal singing system between a group of priests is related to that of groups of priestesses in ancient Egypt where both were characterized by the use of melismata (where many notes were sung over one of the seven vowels which were called 'magic vowels', used to express feelings of piety and humility on religious occasions). Both were characterized also by the use of professional blind singers and percussion instruments in the performance of religious music.

[taken from: Coptic Music]The Ancient Music of the Coptic Church - 1931 Oxford lecture by Ernest Newlandsmith

Music of the Dark Ages (475-1000) ::

386: Hymn singing introduced by Ambrose, Bishop of Milan.

450: First use of alternative singing between the precentor and community at Roman Church services, patterned after Jewish traditions.

Liturgy - a history of early forms of worship in the Catholic Church.

c. 500: Foundation of Schola Cantorum for church song, Rome by Pope Gregory.

500: Boethius writes De Institutione Musica.

500: In Peru, flutes, tubas and drums in use.

From the original Andean people, the Incas inherited an astonishing variety of wind instruments, including flutes and panpipes of all types and sizes. Inca military musicians also played conch-shell trumpets and timpani. In the ruins and ancient graveyards on the Peruvian coast, small broken clay panpipes and whistle-like flutes producing pentatonic, diatonic, or exotic scales are still found. Although grave robbers usually discard the instruments, archeologists often recover them.

In Xochitl, In Cuicatl: Hallucinogens and Music in Mesoamerican Amerindian Thought.

521: Boethius introduces Greek musical letter notation to the West.

for more information: Origin of Music Notation.

600: Pope Gregory orders the compilation of church chants, titled Antiphonar.

Chant was the true basic ancestor of western tonal music. In a process that lasted several centuries, the Roman Church absorbed and compiled liturgical melodies from diverse European regions. Those different dialects or styles included, among others, Gallican, Beneventan, Visigothic or Mozarabic, and Ambrosian Chant. The whole repertory was reorganized by Pope Gregory II (715-31), after whom the expression Gregorian Chant was coined.

for more information: Antiphonary.

seventh century: Musica rythmica and Musica organica by St. Isidore of Seville (c. 560-636)

Although secular music experienced its most dramatic expansion in the eleventh century, and significant historical documentation is lacking before that time, it would be a mistake to think that secular music did not enjoy popularity before the High Middle Ages. The music of the people, musica civilis, was sufficiently common to draw disparagement from the early Church fathers and in the seventh century, another Church Father, St. Isidore of Seville, the first Christian writer to essay the task of compiling for his co-religionists a summa of universal knowledge, made a study of musical instruments in two treatises. Musica rythmica investigated stringed and percussion instruments, while Musica organica covered the wind instruments. These studies included many instruments used only in secular music.

[taken from: The End of Europe's Middle Ages]

609: The crwth, a Celtic string instrument, appears.

The crwth is a medieval bowed lyre and ranks as one of Wales's most exotic traditional instruments. it has six strings tuned g g' c' c d' d'' and a flat bridge and fingerboard. the gut strings produce a soft purring sound, earthy but tender. the melody is played on four of the six strings, with the other two acting as plucked or bowed drones and the octave doublings producing a constant chordal accompaniment. The crwth has been played in Wales in one form or another since Roman times. It was an instrument of the highest status during the middle ages whose best players could earn a stable income in the courts of the Welsh aristocracy. Crwth players had to undergo years of apprenticeship and memorise twenty-four complex pieces of music.

[taken from: About the crwth]for more information: The Crwth.

sixth century: Neums and neuming.

The earliest systems of musical notation were developed between 1500 and 3000 years ago by the Greeks. These schemes were generally based on letters of the Greek alphabet. This had several problems: the melody of the song could be confused with its words, the system was not very accurate, and it was immensely complicated. Neumes and neuming were developed to overcome these problems. Neumes were small marks placed above the text to indicate the 'shape' of a melody. As a form of notation, they were initially even less effective than the letter-based systems they replaced, but they were unambiguous and took very little space, and so they survived when other systems failed. Our modern musical notation is descended from neumes. The psalms provide clear evidence on Biblical texts being sung. Many of the psalms indicate the tune used for them. There are places in the New Testament (e.g. Mark 14:26 and parallels, Acts 16:25) which apparently refer to the singing of psalms and biblical texts. But we have no way to know what tunes were used. This was as much a problem for the ancients as it is for us. By the ninth century they were beginning to develop ways to preserve tunes. We call the early form of this system neuming, and the symbols used nuemes (both from Greek pneuma).

The earliest neumes (found in manuscripts such as Y/044) couldn't really record a tune. Neither pitch nor duration was indicated, just the general 'shape' of the tune. Theoretically only two symbols were used: "Up" (the acutus, originally symbolized by something like /), and the "Down" (gravis, \). These could then be combined into symbols such as the "Up-then-down" (^). This simple set of symbols wasn't much help if you didn't know a tune but could be invaluable if you knew the tune but didn't quite know how to fit it to the words. It could also jog your memory if you slipped a little.

Neumes were usually written in green or red ink in the space between the lines of text. They are, for obvious reasons, more common in lectionaries than in continuous-text manuscripts. As the centuries passed, neuming became more and more complex, adding metrical notations and, eventually, ledger lines. The picture below (a small portion of chapter 16 of Mark from the tenth-century manuscript 274) shows a few neumes in exaggerated red. In this image we see not only the acutus and the gravis, but such symbols as the podatus (the J symbol, also written !), which later became a rising eighth note.

By the twelfth century, these evolved neumes had become a legitimate musical notation, which in turn evolved into the church's ancient" plainsong notation" and the modern musical staff. All of these forms, however, were space-intensive (plainsong notation took four ledger lines, and more elaborate notations might take as many as fifteen), and are not normally found in Biblical manuscripts (so much so that most music history books do not even mention the use of neumes in Biblical manuscripts; they usually start the history of notation around the twelfth century and its virga, punctae, and breves). The primary use of neumes to the Biblical scholar is for dating: If a manuscript has neumes, it has to date from roughly the eighth century or later. The form of the neumes may provide additional information about the manuscript's age.

[taken from: Neumes]Gregorian Chant Notation - Neumes

744: Singing school established at the Monastery of Fulda.

Established in 743/44, Fulda was a Benedictine monastery in Hesse-Nassau that grew rich from pilgrimages to the grave of St. Boniface and gained renown as an intellectual centre as its library grew. Sts. Boniface and Sturmius founded the house as a training school and base for missionaries whom Charlemagne sent to the Saxons. Soon after the death of Boniface, Fulda became an important destination for pilgrims, and about a century after its founding, the abbot Rabamus Maurus increased the intellectual riches of the monastery through its school, scriptorium, and library, which, at its peak, held approximately 2,000 manuscripts. It preserved works such as Tacitus' Annales, and the monastery is considered the cradle of Old High German literature. The abbots of Fulda became, in the tenth century, the abbot general of the Benedictines in Germany and Gaul. In the twelfth century, they became imperial chancellors and in the thirteenth century, princes of the empire. Fulda was the center of monastic reform during the reign of Henry II.

750: Gregorian church music is sung in Germany, France, and England.

Charlemagne (742-814) was an enthusiastic lover of Church music, and especially of this style which he had learnt to know in Rome. In his own chapel he carefully noted the powers of all the priests and singers, and sometimes acted as choir-master himself, in which capacity he proved a very strict, often severe master, He extinguished the last remnants of the Ambrosian style at Milan, and it was with his approval that Pope Leo III (795-810) imposed a penalty of exile or imprisonment on any singer who might deviate from the orthodox Cantus firmus et choralis. He not only founded schools of music in France, but throughout Germany, at Fulda, Mayence, Treves, Reichenau, and other places. Trained singers from the famous choirs in Rome were sent for to take charge of these institutions, and seem to have been not a little shocked at first by the barbarism of their pupils. One says that their notion of singing in Church was to howl like wild beasts; while another, Johannes Didimus, in his 'Life of Gregory', affirms that, "these gigantic bodies, whose voices roar like thunder, cannot imitate our sweet tones, for their barbarous and ever-thirsty throats can only produce sounds as harsh as those of a loaded wagon passing over a rough road."

757: Wind organs, originally from Byzantium, start to replace water organs in Europe.

Evidence of the first purely pneumatic organ is found on an obelisk erected at Byzantium before 393 AD. Byzantium became the centre of organ building in the Middle Ages, and in 757 Constantine V presented a Byzantine organ to Pepin the Short. This is the earliest positive evidence of the appearance of the organ in Western Europe. By the tenth century, however, organ building had made considerable progress in Germany and England. The organ built c. 950 in Winchester Cathedral is said to have had 400 pipes and 26 bellows and required two players and 70 men to operate the bellows. The keyboard, or manual, was a creation of the thirteenth century, making possible the performance of more complex music. The earliest extant music written specifically for organ, dating from the early fourteenth century, gives evidence that by then the manuals of the organ had full chromatic scales, at least in the middle registers. Organs in the Middle Ages already had several ranks of pipes, each key causing a number of pipes to sound simultaneously. All were diapasons, or principals, the pipes of timbre characteristic only of the organ, and the various pipes controlled by one key were tuned to the fundamental and several harmonics of a given tone.

781: English monk Alcuin (c. 732804) meets Charlemagne; Alcuin encouraged study of liberal arts, influencing the Carolingian Renaissance. Alcuin was largely responsible for the revision of the Church Liturgy during the reign of Charlemagne.

790: Schools for church music established by Charlemagne (742-814) at Paris, Cologne, Soissons and Metz, all supervised by the Schola Cantorum in Rome.

The rise of secular music was aided by the development of a corpus of Latin lyrical literature during the reign of Charlemagne that included a collection of secular and semi-secular songs. Some scholars even played at setting to music the works of classical poets, such as Horace, Virgil, Cassiodorus, and Boethius.

800: Charlemagne crowned first Holy Roman Emperor: the beginning of the Carolingian Renaissance

c. 800: Hildebrandslied

There are no written monuments before the eighth century. The earliest written record in any Germanic language, the Gothic translation of the Bible by Bishop Ulfilas, in the fourth century, does not belong to German literature. It is known from Tacitus that the ancient Germans had an unwritten poetry, which among them supplied the place of history. It consisted of hymns in honour of gods, or songs commemorative of the deeds of heroes. Such hymns were sung in chorus on solemn occasions, and were accompanied by dancing; their verse form was alliteration. There were also songs, not choric, but sung by minstrels before kings or nobles, songs of praise, besides charms and riddles. During the great period of the migrations poetic activity received a fresh impulse. New heroes, like Attila (Etzel), Theodoric (Dietrich), and Ermanric (Ermanrich), came upon the scene; their exploits were confused by tradition with those of older heroes, like Siegfried. Mythic and historic elements were strangely mingled, and so arose the great saga cycles, which later on formed the basis of the national epics. Of all these the Nibelungen saga became the most famous, and spread to all Germanic tribes. Here the most primitive legend of Siegfried's death was combined with the historical destruction of the Burgundians by the Huns in 435, and affords a typical instance of saga-formation. Of all this pagan poetry hardly anything has survived. The collection that Charlemagne caused to be made of the old heroic lays has perished. All that is known are the Merseburger Zaubersprüche, two songs of enchantment preserved in a manuscript of the tenth century, and the famous Hildebrandslied, an epic fragment narrating an episode of the Dietrich saga, the tragic combat between father and son. It was written down after 800 by two monks of Fulda, on the covers of a theological manuscript. The evidence afforded by these fragments, as well as such literature as the Beowulf and the Edda, seems to indicate that the oldest German poetry was of considerable extent and of no mean order of merit.

[taken from: German Literature]

850: Setting out of Church modes in Alia Musica.

c. 870: Musica enchiriadis

Although singers probably improvised polyphony long before it was first notated, an anonymous treatise from the ninth century, Musica enchiriadis (Music Handbook, 870), is the earliest that describes two types of early organum: parallel motion in which a plainsong melody (vox principalis) is duplicated a perfect fourth or fifth below by an organal voice (vox organalis), with duplication of either voice at the octave possible; or, Oblique motion in which the organal voice remains on the same pitch in order to avoid tritones against the principal voice.

889: Regino, Abbot of Prüm, writes his treatise on church music: De harmonica institutione.

Reginon or Regino of Prüm, medieval chronicler, was born at Altripp near Speyer, and was educated in the monastery of Prüm. Here he became a monk, and in 892, just after the monastery had been sacked by the Danes, he was chosen abbot. In 899, however, he was deprived of this position and he went to Trier, where he was appointed abbot of St Martin's, a house which he reformed. He died in 915, and was buried in the abbey of St Maximin at Trier, his tomb being discovered there in 1581. Reginon wrote a Chronicon, dedicated to Adalberon, bishop of Augsburg (d. 909), which deals with the history of the world from the commencement of the Christian era to 906, especially the history of affairs in Lorraine and the neighbourhood. The first book (to 741) consists mainly of extracts from Bede, Paulus Diaconus and other writers; of the second book (741-906) the latter part is original and valuable, although the chronology is at fault and the author relied chiefly upon tradition and hearsay for his information. The work was continued to 967 by a monk of Trier, possibly Adalbert, archbishop of Magdeburg (d. 981). The chronicle was first printed at Mainz in 1521; another edition is in Band I of the Monumenta Germaniae historica Scriptores (1826); the best is the one edited by F Kurze (Hanover, 1890). It has been translated into German by W Wattenbach (Leipzig, 1890). Reginon also drew up at the request of his friend and patron Radbod, archbishop of Trier (d. 915) a collection of canons, Libri duo de synodalibus causis et disciplines ecclesiasticis, dedicated to Hatto I, archbishop of Mainz; this is published in Tome 132 of J P Migne's Patrologia Latina. To Radbod he wrote a letter on music, Epistola de harmonica institutione, with a Tonarius, the object of this being to improve the singing in the churches of the diocese. The letter is published in Tome I of Gerbert's Scriptores ecclesiastici de musica sacra (1784), and the Tonarius in Tome II of Coussemaker's Scriptores de musica mediiaevi.

890: Ratbert of St. Gall born, hymn writer and composer.

The Abbey of St. Gall (in German, St. Gallen), founded in 613, is situated in Switzerland, Canton St. Gall, 30 miles southeast of Constance. For many centuries it was one of the chief Benedictine abbeys in Europe. It was named after Gallus, an Irishman, the disciple and companion of St. Columbanus in his exile from Luxeuil. When his master went on to Italy, Gallus remained in Switzerland, where he died about 646. A chapel was erected on the spot occupied by his cell, and a priest named Othmar was placed there by Charles Martel as custodian of the saint's relics. Under his direction a monastery was built, many privileges and benefactions being upon it by Charles Martel and his son Pepin, who, with Othmar as first abbot, are reckoned its principal founders. By Pepin's persuasion Othmar substituted the Benedictine rule for that of St. Columbanus. He also founded the famous schools of St. Gall, and under him and his successors the arts, letters, and sciences were assiduously cultivated. The work of copying manuscripts was undertaken at a very early date, and the nucleus of the famous library gathered together. The abbey gave hospitality to numerous Anglo-Saxon and Irish monks who came to copy manuscripts for their own monasteries. Two distinguished guests of the abbey were Peter and Romanus, chanters from Rome, sent by Pope Adrian I at Charlemagne's request to propagate the use of the Gregorian chant. Peter went on to Metz, where he established an important chant-school, but Romanus, having fallen sick at St. Gall, stayed there with Charlemagne's consent. To the copies of the Roman chant that he brought with him, he added the "Romanian signs", the interpretation of which has since become a matter of controversy, and the school he started at St. Gall, rivalling that of Metz, became one of the most frequented in Europe. The chief manuscripts produced by it, still extant, are the Antiphonale Missarum (no. 339), the Antiphonarium Sti. Gregorii (no. 359), and Hartker's Antiphonarium (nos. 390-391), the first and third of which have been reproduced in facsimile by the Solesmes fathers in their Paléographie Musicale.

[taken from: Abbey of St. Gall]By the late 900s, the Abbey of St. Gall had a library of 600 books. The city of Córdoba, in the north-central part of Andalusia, with its population of possibly 500,000 people, 1,600 mosques (including the great Mosque of Córdoba, considered by some architectural historians to be the most spectacular Islamic building in the world), 900 public baths and 80,455 shops, had a library with 400,000 volumes and was so great a cultural and intellectual centre that the Saxon nun Roswitha of Gandersheim (c.935-c.1000 AD) described the city (at that time) as the ornament of the world.

tenth century: The Eisteddfods of the Middle Ages.

Many claim that an eisteddfod took place during the reign of King Cdwaladr (who died in 664). The Juvencus Codex (ninth century), in which a number of Welsh stanzas are found, makes it clear that Welsh lyric poetry was being written at this time at the latest. In the tenth century, we find the Welsh Laws, Leges Wallicae, codified by Hywel Dda, in which is mentioned that "the king has twenty-four officers of the court", one of them is "the Bard of the Household [Bardd Teulu]". In various writings it is said: "There are three legal harps; the kings harp [telyn e brenhyn]; the harp of a chief of song [a thelyn penkerd]; and a harp of a gwrda [a thelyn gurda]". According to the Dimetian and Gwentian Codes the chief of song is "a bard who shall have gained a chair". He was richly rewarded and enjoyed many privileges. By the 'chief of song' (Penkerdd) they probably meant "the head of the whole bardic community within the limits of the kingdom". In 1070, Bleddyn ap Kynfyn is said to have held an eisteddfod lasting 40 days. "Degrees were conferred on chiefs of song, and gifts and presents made to them, as in the time of the Emperor Arthur".

[taken from:The Eisteddfods of the Middle Ages]

c. 950: Organ with 400 pipes finished at Winchester Monastery, England.

In about the year 950 a famous organ was built at Winchester Cathedral. A contemporary poem described it (see reference below), and it was an outstanding example of an early, large Blokwerk organ. There were 26 bellows supplying wind to an undivided chest of 400 pipes; the keyboard (or keyboards) had a 40-note compass, and required two players, possibly owing to the clumsy nature of the playing technique. Each key played ten ranks of pipes.

for more information: The Organ in Medieval Literature

980: Antiphonarium Codex Montpellier written, important musical manuscript.

Music of the High Middle Ages (1000-1350) ::

early eleventh century:

- Christianity began to penetrate Finland from the West in some form probably as early as in the eleventh century, imported by merchants, Christianized Vikings and German missionaries. At about the same time, Orthodox Christianity from Novgorod began to make inroads in the eastern reaches of Finland. Tradition holds that the first Crusade to Finland was undertaken around the year 1155, by which time Christianity already had a foothold in the land. Finland was finally incorporated into the Catholic Church and the Kingdom of Sweden when the Pope granted King Erik Knutsson permission to take Finland under his protection in 1216. With Christianity came liturgical chant, Gregorian (Latin) chant from the West and Orthodox (Byzantean) chant from the East. Although the Western influence is easier to trace, its progress is by no means clear. Ilkka Taitto, the leading Finnish scholar in the field, has divided the history of Latin chant in Finland into three periods: 1) the missionary period, from c. 1100 to 1330; 2) the established repertoire period, from c. 1330 to 1530; and 3) the early Lutheran period, from c. 1530 to 1640. By contrast, it is almost impossible to estimate with any precision when polyphonic singing arrived in Finnish churches perhaps in the fourteenth century, in the form of simple types of organum. We also do not know when the first organs appeared in Finnish churches this may have happened as late as in the sixteenth century, and in any case initially only very few churches acquired organs.

- Finnish Music Information Centre from which this extract has been taken

early eleventh century: The songs known as Carmina Burana are collected.

The Carmina Burana is a collection of poems, songs, and short plays found in Benediktbeuern, a Benedictine abbey about 100 km south of Munich, in 1803. This manuscript was of thirteenth-century German origin and contained approximately 250 poems, and other pieces. When Johann Andreas Schmeller published the collection in 1847, he gave it the title of Carmina Burana. This name means 'songs of Beuren,' though it has since been discovered that the manuscript did not originate there, and may have come from Seckau. Although the manuscript dates from the thirteenth century, most of it was written in the twelfth. This was a period of peace and prosperity in comparison with the years of war which preceded it. The majority of the Carmina Burana is written in Latin, which was the standard language of literacy at the time. There are, however, many pieces written in Middle High German, which shows the blossoming influence of vernacular languages on literature which began during this time. This collection is the most important and comprehensive source for both early German literature and Goliardic verse, the secular poetry of the Goliards serving as a counter-weight in an age of faith. Goliardic verse developed with the beginning of European universities in the twelfth century. It flourished for more than a century written by itinerant clerks and monks who wrote a style of secular lyric poetry commending the pleasures of life - wine, women and song - in a humourous and satirical manner. The Church, whose officials were often the butt of these ribald commentaries, was not amused, and subject to ecclesiastical suppression, the movement had disappeared sometime during the fourteenth century.

-

for more information: The Real Goliards - Historical Facts and Links About the Real Goliards

early eleventh century: Guido d'Arezzo develops an improved form of musical notation

It is likely that Guido was born in France. He served as a Benedictine monk then traveled in 1025 to work for Bishop Theobald in Arezzo, Italy where he lived for some years. Although Guido was not a composer, he is included here because his contributions as an early music theorist made it possible for early composers to begin recording their work in manuscript. Around 1025 Guido created a system of musical notation using a 4-line staff which has evolved into the system we use today. The importance of this work is enormous. Before Guido's invention of musical notation, every singer had to memorize the entire chant repertoire. Those singers then went on to teach the next generation. Small errors in memory or differences of taste caused the chants to change over the years and no two singers would learn a chant precisely the same way. Notation made it possible to record a chant in a definitive form for posterity and easier communication. Guido's last recorded activity is in 1033. His actual death date is unknown.

for more information: Why middle C?

10th & 11th centuries: ars antiqua - (Lat., the old art)

Contrary to the description of organum given in the ninth century handbook Musica enchiriadis, The Winchester Troper, an example of a later form, is characterised as follows:

(a) the vox principalis becomes the lower voice.

(b) the vox organalis becomes the upper voice.

(c) the two voice parts often cross.

(d) perfect consonances (unison, octave, fourth, and fifth) continue to be favoured; other intervals occur incidentally and infrequently.

(e) sections of both the Mass and Divine Office, that normally would have been sung by soloists in plainchant, become troped, i.e. they receive polyphonic treatment.

The Winchester Troper is the earliest known practical source (i.e. not a treatise) but its voices are notated in unheighted neumes without staff lines, so that only pieces that also occur in later manuscripts can be reconstructed.

1054: The Great Schism divides western and eastern Christianity

1066: Battle of Hastings; William of Normandy conquers England.

10661077: Bayeux Tapestry.

10951099: Crusades; Jerusalem captured 1099.

1105: Fall of Toledo